May 25

Beyond the Fever

Why Understanding McGreer Criteria Protects Residents in Aged Care

Allison McGeer

In Aged Care Facilities (ACF), identifying infections in older adults can be very challenging. Residents often have multiple and complex health issues and may not show the classic signs of an illness that we are used to seeing in younger populations. Fever might be subtle, or symptoms might manifest as something less obvious, like a behaviour change. This is where the McGeer Definitions come in, providing a standardised framework specifically designed for infection surveillance in this specific setting. As there are limitations in acute care definitions, McGeer has been developed to help healthcare professionals consistently recognise potential infections, ensuring more accurate data collection and better infection control strategies. Join us as we explore in this blog how looking "beyond the fever", using these specialised criteria, is essential for the safety of our residents in Aged Care.

The Origins and Purpose of McGeer Criteria

The journey to standardised infection surveillance in ACFs began because a clear need was recognised: there wasn't a consistent way to define infections in these settings. The McGeer criteria originated in the late 1980s and were published in the American Journal

of Infection Control in 1991. This was the result of collaborative work led by Dr. Allison McGeer and a team of experts, including infectious diseases physicians, geriatricians, and infection control nurses with hands-on experience in long-term care facilities. They adapted existing surveillance models, like the CDC's National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance (NNIS) system, but made careful modifications to fit the specific needs of ACFs.

The primary purpose was clear: to establish a consistent, reliable framework for both infection surveillance and research studies in ACFs. This included the specific aim to create a standardised approach to identifying infections and supporting robust research, allowing facilities to compare infection rates meaningfully. They were then better able to evaluate how well infection control programs were working, and with a more reliable way to measure outcomes. Developing these criteria early on showed foresight about the growing importance of the ACF sector and its unique infection control challenges. This collaborative, expert-driven process gave the McGeer criteria strong credibility right from the beginning.

The primary purpose was clear: to establish a consistent, reliable framework for both infection surveillance and research studies in ACFs. This included the specific aim to create a standardised approach to identifying infections and supporting robust research, allowing facilities to compare infection rates meaningfully. They were then better able to evaluate how well infection control programs were working, and with a more reliable way to measure outcomes. Developing these criteria early on showed foresight about the growing importance of the ACF sector and its unique infection control challenges. This collaborative, expert-driven process gave the McGeer criteria strong credibility right from the beginning.

Understanding McGeer's Constitutional and General Criteria

One of the brilliant aspects of the McGeer criteria is their recognition that infections in older adults often don't present with dramatic, localised symptoms as in younger adults. Instead, systemic changes can be the first or only clue. This is why the criteria include Constitutional Criteria – general signs and symptoms indicating a body-wide response to an infection. These are crucial because they capture those subtle yet significant shifts in a resident's health.

The main constitutional criteria include:

The main constitutional criteria include:

- Fever: Defined specifically as a single high oral temperature (>37.8°C / >100°F), or repeated lower oral or rectal temperatures (>37.2°C / 99°F or >37.5°C / 99.5°F), or even just a notable rise (>1.1°C / 2°F) from the individual resident's baseline temperature, regardless of where it's measured.

- Leukocytosis: Defined as either a total leukocyte count over 14,000 cells/mm³ or a "left shift" in the differential count, meaning more than 6% band neutrophils or at least 1,500 bands/mm³.

- Acute change in mental status from the baseline: Requires all four of these components: an acute onset, a fluctuating course, inattention, AND either disorganised thinking or an altered level of consciousness. The detailed definition for mental status changes is vital because delirium is a common, and often the sole, sign of infection in ACF residents.

- Acute functional decline: Defined as a new increase of 3 points or more from their baseline score on a specific 7-item Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale. The scale covers bed mobility, transferring, dressing, eating, etc., indicating the level of dependence.

By including these non-specific indicators and providing clear definitions for terms like "Acute Onset" and "Fluctuating", McGeer ensures a more consistent and reliable way to identify potential infections, especially when classic signs are absent.

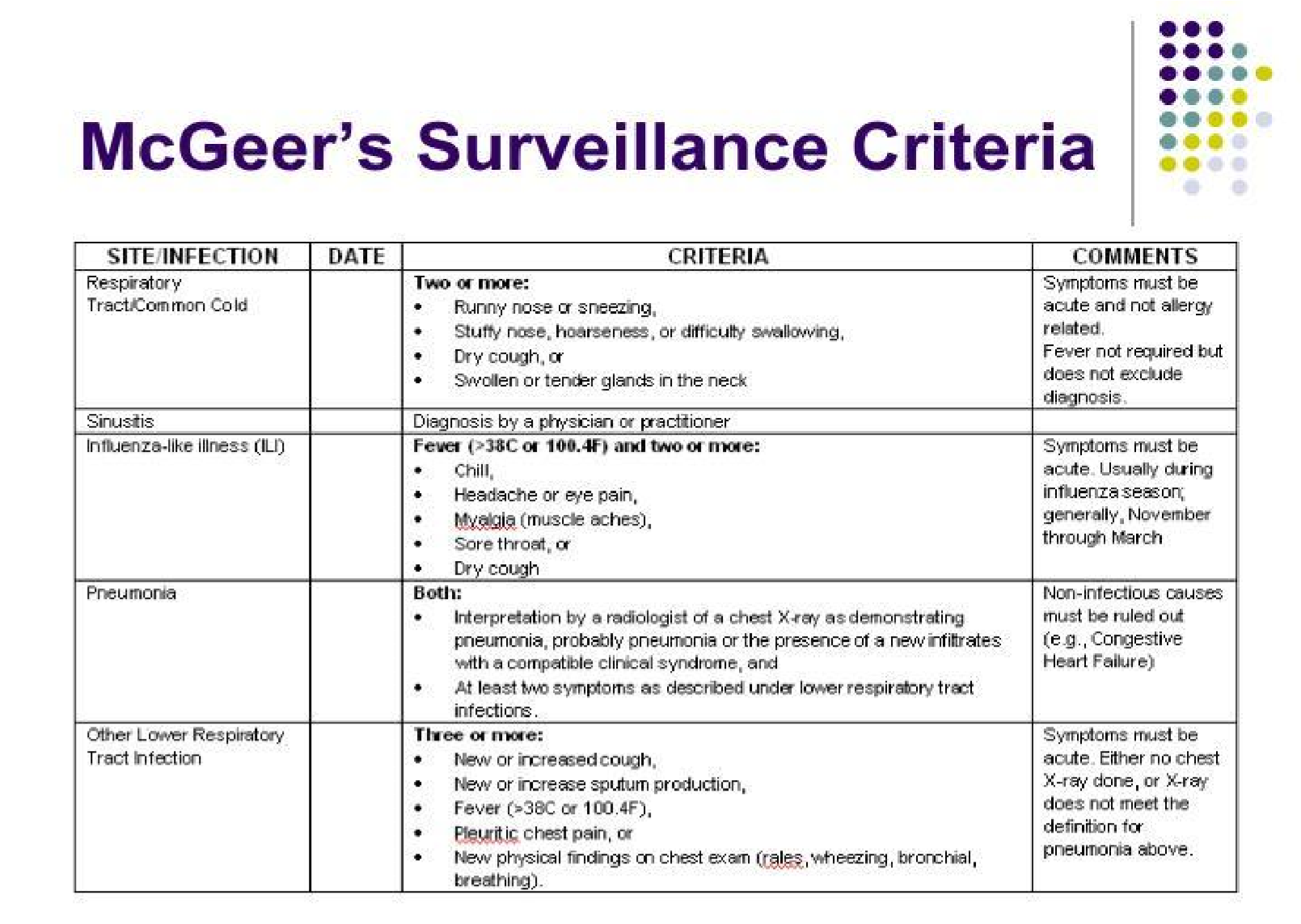

A Look at Syndrome-Specific McGeer Definitions

While constitutional symptoms raise a flag, the McGeer criteria take a step further by providing detailed definitions for common types of infections seen in ACFs. These syndrome-specific definitions combine clinical observations with laboratory or radiographic evidence to pinpoint the source of the infection.

Examples include:

Examples include:

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): Definitions differ based on whether a resident has an indwelling urinary catheter or not. For residents without a catheter, defining a UTI requires both clinical signs (like acute dysuria or specific urinary symptoms with/without fever/leukocytosis) AND microbiological evidence (specific bacterial counts in a urine sample). For catheterised residents, clinical signs include fever/rigours/hypotension or acute mental status/functional decline plus leukocytosis (with no other diagnosis), or localised signs, and microbiological evidence (a culture from a catheter specimen). This emphasis on lab confirmation is vital because asymptomatic bacteriuria is common in older adults, and over-treating it contributes to antibiotic resistance.

- Respiratory Tract Infections (RTIs): Definitions exist for Common Cold/Pharyngitis, Influenza-like Illness, Pneumonia, and Lower RTIs (Bronchitis/Tracheobronchitis). Pneumonia specifically requires a chest X-ray showing pneumonia or a new infiltrate plus respiratory symptoms and a constitutional criterion. Lower RTIs require no chest X-ray or a negative one, respiratory symptoms, and a constitutional criterion.

- Gastrointestinal Tract Infections (GITIs): Definitions cover Gastroenteritis, Norovirus Gastroenteritis, and Clostridioides difficile Infection (CDI). Norovirus and CDI require specific lab confirmation. The inclusion of these highlights their significant impact and potential for outbreaks in ACFs. For Norovirus, the criteria even include features to assume an outbreak if lab confirmation is unavailable, but specific outbreak characteristics are present.

- Skin, Soft Tissue, and Mucosal Infections (SSTIs): These definitions often combine clinical signs with diagnosis or lab confirmation. For example, Cellulitis

or

Wound Infection is defined by pus or at least four signs plus a constitutional criterion. Reactivations of conditions like Herpes Simplex ("cold sores") or Varicella Zoster ("shingles") are generally not considered healthcare-associated infections in these criteria, as they cannot be characterised as “new” infections. Surveillance tends to focus on the newly acquired infections within the facility.

These detailed definitions help distinguish specific infection types and guide surveillance efforts.

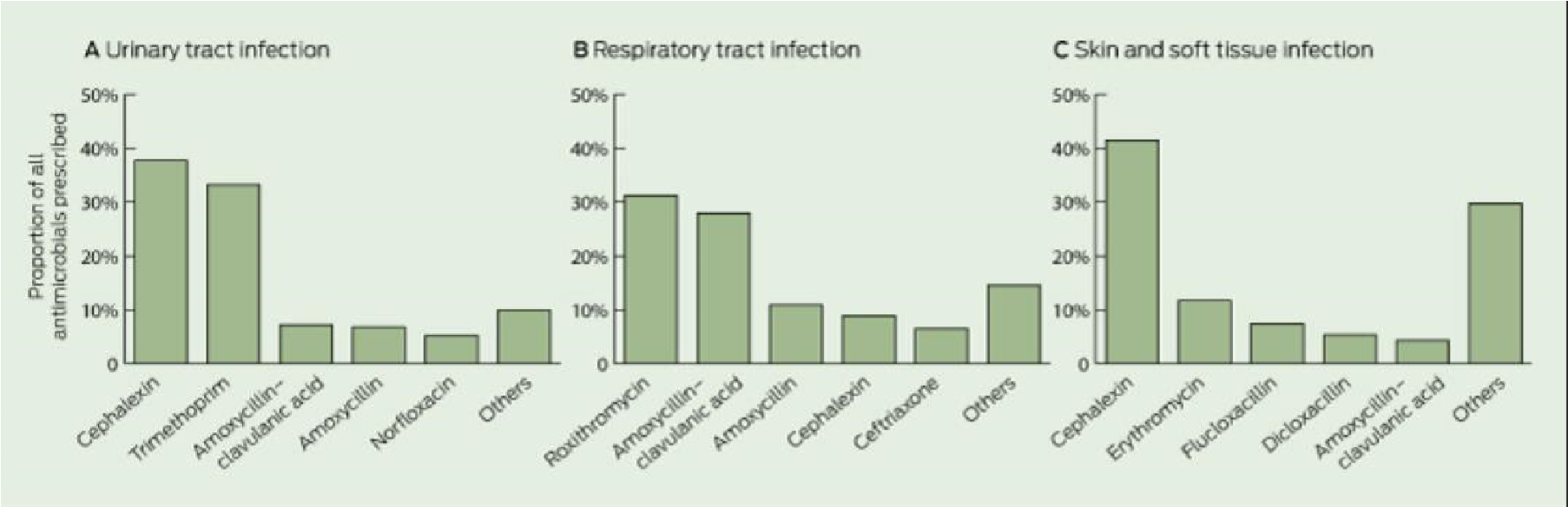

How McGeer Improves Infection Control and Antibiotic Stewardship

So, how do these detailed definitions make a difference in the real world of an aged care facility? Their impact is significant and far-reaching. Because McGeer provides a common language and consistent criteria, facilities can collect comparable data on infections from other facilities. With consistent data, facilities can produce a benchmark for their infection rates against others, identify concerning trends and patterns, and accurately evaluate the effectiveness of their infection prevention and control programs. This will allow for data-driven decisions, making interventions more targeted and effective.

Perhaps one of the most vital impacts is on Antibiotic Stewardship Programs. In ACFs, accurately identifying whether a resident truly has an infection requiring antibiotics or is showing non-infectious symptoms is crucial. By providing clear, standardised criteria for identification, McGeer's definitions directly support more appropriate antibiotic prescribing. When staff can confidently determine if surveillance criteria for an infection are met, it guides them and clinicians in deciding if antibiotics are necessary. This is a prime strategy in the fight against antimicrobial resistance, a major health threat globally. Accurate identification means antibiotics are used only when truly needed, minimising risks to the resident and reducing the development of resistant bacteria.

Perhaps one of the most vital impacts is on Antibiotic Stewardship Programs. In ACFs, accurately identifying whether a resident truly has an infection requiring antibiotics or is showing non-infectious symptoms is crucial. By providing clear, standardised criteria for identification, McGeer's definitions directly support more appropriate antibiotic prescribing. When staff can confidently determine if surveillance criteria for an infection are met, it guides them and clinicians in deciding if antibiotics are necessary. This is a prime strategy in the fight against antimicrobial resistance, a major health threat globally. Accurate identification means antibiotics are used only when truly needed, minimising risks to the resident and reducing the development of resistant bacteria.

Evolution, Revisions, and Acknowledging Limitations

No framework stays relevant forever without updates, and the McGeer criteria are no exception to this. To keep pace with new medical knowledge and better diagnostic tools, they underwent a significant revision process in 2012, led by an expert consensus panel. The 2012 revisions incorporated new evidence and aimed to address some limitations of the criteria. For UTIs, there was a stronger emphasis on needing localised urinary symptoms in non-catheterised residents and reinforced recommendations for microbiological confirmation. New surveillance definitions were added for Norovirus gastroenteritis and Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI), reflecting their growing recognition as significant issues in aged care.

However, even with revisions, it's important to acknowledge that the McGeer criteria aren't perfect and have faced criticisms and limitations since their creation. A major challenge is their potential sensitivity and specificity in the elderly population, especially those with cognitive impairment like dementia. Residents with dementia may not be able to articulate symptoms that are central to some McGeer definitions, making their application difficult. Some argue the criteria might be overly sensitive, potentially leading to the overdiagnosis of infection.

Another key limitation is that the McGeer criteria were primarily designed for retrospective surveillance, for counting and tracking infections after they've occurred. This can limit their use in guiding real-time clinical decisions about whether to start antibiotics at the resident’s bedside. This is a key difference when compared to criteria like the Loeb criteria, which were developed specifically to guide the use of an antibiotic based on minimum clinical signs. Studies have shown that McGeer and Loeb criteria don't always agree with each other.

However, even with revisions, it's important to acknowledge that the McGeer criteria aren't perfect and have faced criticisms and limitations since their creation. A major challenge is their potential sensitivity and specificity in the elderly population, especially those with cognitive impairment like dementia. Residents with dementia may not be able to articulate symptoms that are central to some McGeer definitions, making their application difficult. Some argue the criteria might be overly sensitive, potentially leading to the overdiagnosis of infection.

Another key limitation is that the McGeer criteria were primarily designed for retrospective surveillance, for counting and tracking infections after they've occurred. This can limit their use in guiding real-time clinical decisions about whether to start antibiotics at the resident’s bedside. This is a key difference when compared to criteria like the Loeb criteria, which were developed specifically to guide the use of an antibiotic based on minimum clinical signs. Studies have shown that McGeer and Loeb criteria don't always agree with each other.

McGeer's Enduring Value and Future Directions

Despite their limitations, the McGeer definitions have undeniably left a deep mark on infection surveillance in ACFs. They provided a critical, standardised framework where none truly existed before. This standardisation has significantly improved our understanding of the true burden of infections, fuelled valuable research, and directly supported the implementation of essential infection control practices.

As the field continues to evolve, so too will the need for ongoing research and refinement. Future efforts could focus on confirming the revised criteria, developing more tailored criteria specifically for residents with significant cognitive impairment, exploring how objective measures like biomarkers could be incorporated, and working towards greater harmonisation with other national surveillance systems like the CDC's NHSN definitions. While different criteria like NHSN are being increasingly adopted by facilities, the historical and ongoing value of McGeer as a comprehensive framework for understanding infection patterns remains.

Ultimately, maintaining a strong commitment to robust and accurate infection surveillance in ACFs, guided by standardised criteria like McGeer, is crucial. It's about continually striving to understand, prevent, and manage infections more effectively, therefore improving resident safety and achieving better healthcare outcomes for those who call these facilities home.

This blog is for those who have enquired about the McGeer criteria and wanted to know more about it. There is more information on the HUB for your reference, including the McGeer surveillance tool.

As the field continues to evolve, so too will the need for ongoing research and refinement. Future efforts could focus on confirming the revised criteria, developing more tailored criteria specifically for residents with significant cognitive impairment, exploring how objective measures like biomarkers could be incorporated, and working towards greater harmonisation with other national surveillance systems like the CDC's NHSN definitions. While different criteria like NHSN are being increasingly adopted by facilities, the historical and ongoing value of McGeer as a comprehensive framework for understanding infection patterns remains.

Ultimately, maintaining a strong commitment to robust and accurate infection surveillance in ACFs, guided by standardised criteria like McGeer, is crucial. It's about continually striving to understand, prevent, and manage infections more effectively, therefore improving resident safety and achieving better healthcare outcomes for those who call these facilities home.

This blog is for those who have enquired about the McGeer criteria and wanted to know more about it. There is more information on the HUB for your reference, including the McGeer surveillance tool.

Lyndon Forrest

Managing Director | CEO

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

Erica Leadley

Manager, Marketing and Sales

Erica Leadley is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Erica Leadley is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Toni Sherriff

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Julie Hadfield

Accounts & Payroll

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Andrea Murray

Content Editor

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

Personally, I lived in the UK for 10 years. My two children were born in Scotland, and now both are living in Europe, one in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. I live close to Fairlie on the South Island of NZ, a beautiful part of the country, and I love being out of the city.

Princess

Customer Support

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Dianne Newey

Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

In my role, I promote Infection Prevention and Control, to RACF's and disability support services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

Caoimhe (Keva) Stewart

Manager of Customer Service

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Her move from nursing to customer service was driven by her passion for helping others, not just in clinical settings but also in ensuring that people have access to the resources and support they need. Now, Caoimhe applies her problem-solving skills, attention to detail, and communication expertise to her role, helping to create a positive and effective learning environment for all students.

Outside of work, Caoimhe enjoys travelling, staying active, and catching up with friends on the weekends. Whether in healthcare or customer service, she’s dedicated to making a meaningful difference and supporting people in their personal and professional growth.