Sep 18

Flu Outlook for 2026

Australia and New Zealand Aged Care Readiness

As we are enjoying spring in the Southern Hemisphere, efforts are underway to predict the strains of influenza circulating in the Northern Hemisphere, which will determine our 2026 flu vaccine for next winter. It's essential to protect everyone, especially the older people in our care.

As healthcare professionals committed to the well-being of residents in aged care facilities across Australia and New Zealand, you are at the forefront of public health. With the 2026 influenza season on the (far) horizon, understanding the science behind flu vaccine selection, the implications of circulating viral strains, and the insight from the Northern Hemisphere is not just theoretical – it's vital for proactive planning and protecting our most vulnerable populations. This blog will clarify the complex global process and outline its implications for your important work.

The Annual Arms Race: How the 2026 Flu Vaccine is Chosen

Every year, choosing influenza vaccine strains is a complex global task, often called a race against a moving target. This ongoing effort is driven by the influenza viruses' quick ability to change.

Influenza viruses, members of the Orthomyxoviridae family, are primarily classified into three types: influenza A, B, and C. Their ability to evade the human immune system depends on two surface proteins: haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). Antibodies target these antigens, and alterations in their structure can diminish existing immunity.

The most common form of viral change is antigenic drift. This involves small, continuous mutations to the HA and NA antigens, gradually producing new variant strains. While some cross-protection from previous immunity may exist, the cumulative effect of these small changes means a new vaccine is needed each year. This is the fundamental reason why a seasonal flu shot is required annually.

In contrast, antigenic shift is a significant and sudden change that can lead to the emergence of a new influenza A subtype. This can happen when gene segments are exchanged between influenza A viruses, often involving strains that infect both humans and animals (such as birds). An antigenic shift can produce a virus so different that most people have little to no existing immunity, with the potential to cause a worldwide pandemic. While both influenza A and B viruses undergo antigenic drift, only influenza A viruses are known to experience antigenic shift.

To continuously monitor these viral changes and select the appropriate strains for vaccines, a global collaboration known as the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) functions as an intricate "assembly line" for public health. This network includes National Influenza Centres (NICs) in over 100 countries, such as Australia’s Doherty Institute and New Zealand's ESR. These NICs collect and test respiratory specimens, carrying out preliminary analysis to identify influenza viruses. Representative clinical specimens and isolated viruses are then sent to six WHO Collaborating Centres (WHOCCs) worldwide, including the one at the Doherty Institute in Australia, for more detailed antigenic and genetic analysis. These WHOCCs evaluate circulating viruses and the suitability of existing vaccine strains. Ultimately, Essential Regulatory Laboratories (ERLs) produce reagents and candidate vaccine viruses for manufacturing. This coordinated system acts as an "effective early warning system" for new viral changes.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) holds two technical consultations each year to recommend vaccine composition: one in February for the Northern Hemisphere (NH) season and another in September for the Southern Hemisphere (SH) season. For the SH 2026 season, the recommendation will be made in September 2025. This staggered cycle allows the Southern Hemisphere, which follows the Northern Hemisphere's season, to utilise the latest data on circulating strains.

For the 2026 season, the influenza vaccines available in Australia and New Zealand will be quadrivalent, meaning they are designed to protect against four inactivated influenza virus strains: two influenza A and two influenza B strains. This formulation is a public health standard, providing broad protection against the most prevalent circulating viruses. Beyond the traditional egg-based approach, manufacturing has evolved to include cell-based production methods, which can benefit individuals with egg allergies and potentially allow for faster production.

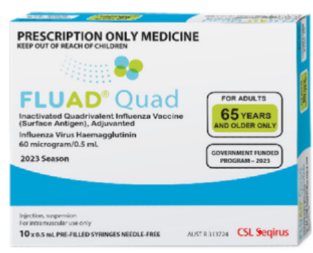

Crucially for aged care, we now have access to enhanced vaccines for older adults, such as the adjuvanted Fluad Quad in Australia and New Zealand, among others. These are recommended over standard-dose options for individuals aged 65 and above to enhance their immune response. This advice is vital for protecting your residents.

Influenza viruses, members of the Orthomyxoviridae family, are primarily classified into three types: influenza A, B, and C. Their ability to evade the human immune system depends on two surface proteins: haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). Antibodies target these antigens, and alterations in their structure can diminish existing immunity.

The most common form of viral change is antigenic drift. This involves small, continuous mutations to the HA and NA antigens, gradually producing new variant strains. While some cross-protection from previous immunity may exist, the cumulative effect of these small changes means a new vaccine is needed each year. This is the fundamental reason why a seasonal flu shot is required annually.

In contrast, antigenic shift is a significant and sudden change that can lead to the emergence of a new influenza A subtype. This can happen when gene segments are exchanged between influenza A viruses, often involving strains that infect both humans and animals (such as birds). An antigenic shift can produce a virus so different that most people have little to no existing immunity, with the potential to cause a worldwide pandemic. While both influenza A and B viruses undergo antigenic drift, only influenza A viruses are known to experience antigenic shift.

To continuously monitor these viral changes and select the appropriate strains for vaccines, a global collaboration known as the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) functions as an intricate "assembly line" for public health. This network includes National Influenza Centres (NICs) in over 100 countries, such as Australia’s Doherty Institute and New Zealand's ESR. These NICs collect and test respiratory specimens, carrying out preliminary analysis to identify influenza viruses. Representative clinical specimens and isolated viruses are then sent to six WHO Collaborating Centres (WHOCCs) worldwide, including the one at the Doherty Institute in Australia, for more detailed antigenic and genetic analysis. These WHOCCs evaluate circulating viruses and the suitability of existing vaccine strains. Ultimately, Essential Regulatory Laboratories (ERLs) produce reagents and candidate vaccine viruses for manufacturing. This coordinated system acts as an "effective early warning system" for new viral changes.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) holds two technical consultations each year to recommend vaccine composition: one in February for the Northern Hemisphere (NH) season and another in September for the Southern Hemisphere (SH) season. For the SH 2026 season, the recommendation will be made in September 2025. This staggered cycle allows the Southern Hemisphere, which follows the Northern Hemisphere's season, to utilise the latest data on circulating strains.

For the 2026 season, the influenza vaccines available in Australia and New Zealand will be quadrivalent, meaning they are designed to protect against four inactivated influenza virus strains: two influenza A and two influenza B strains. This formulation is a public health standard, providing broad protection against the most prevalent circulating viruses. Beyond the traditional egg-based approach, manufacturing has evolved to include cell-based production methods, which can benefit individuals with egg allergies and potentially allow for faster production.

Crucially for aged care, we now have access to enhanced vaccines for older adults, such as the adjuvanted Fluad Quad in Australia and New Zealand, among others. These are recommended over standard-dose options for individuals aged 65 and above to enhance their immune response. This advice is vital for protecting your residents.

The Global Crystal Ball: Why Northern Hemisphere Data Informs the South

The circulation of influenza is a global phenomenon, and the viral patterns of the Northern Hemisphere significantly influence the upcoming season in the Southern Hemisphere. This connection is a well-established epidemiological fact.

Influenza epidemics in temperate regions show a clear winter pattern. While the Northern Hemisphere usually sees cases from November to March, the Southern Hemisphere's season runs from May to September. Human travel is the key connection between the hemispheres. As people from the North travel south, they can carry the dominant influenza strains that developed during the NH's previous winter. These strains then "seed" the upcoming SH flu season. Consequently, analysing the dominant strains and the severity of the NH season is essential for predicting the potential intensity of the next SH season.

Australia and New Zealand are active and essential members of this global surveillance network, with the WHO Collaborating Centre at the Doherty Institute analysing viruses from the Southern Hemisphere and New Zealand's ESR contributing local data to GISRS. This local involvement ensures that public health authorities are actively engaged in monitoring the evolution of viruses.

A fascinating point of divergence arose during the 2024-2025 Northern Hemisphere season: a singular, uniform viral ecology did not materialise.

Influenza epidemics in temperate regions show a clear winter pattern. While the Northern Hemisphere usually sees cases from November to March, the Southern Hemisphere's season runs from May to September. Human travel is the key connection between the hemispheres. As people from the North travel south, they can carry the dominant influenza strains that developed during the NH's previous winter. These strains then "seed" the upcoming SH flu season. Consequently, analysing the dominant strains and the severity of the NH season is essential for predicting the potential intensity of the next SH season.

Australia and New Zealand are active and essential members of this global surveillance network, with the WHO Collaborating Centre at the Doherty Institute analysing viruses from the Southern Hemisphere and New Zealand's ESR contributing local data to GISRS. This local involvement ensures that public health authorities are actively engaged in monitoring the evolution of viruses.

A fascinating point of divergence arose during the 2024-2025 Northern Hemisphere season: a singular, uniform viral ecology did not materialise.

- The United States faced a severe flu season, mainly caused by the H3N2 virus, a subtype often linked to worse outcomes, especially in older adults. The American experience included an unprecedented number of influenza-related deaths among children for a non-pandemic season. An important finding was that 90% of these fatal cases occurred in children who were not fully vaccinated.

- In contrast, parts of Europe experienced a milder season where the H1N1 virus was the main strain, but they still faced a complex and severe respiratory virus season with excess mortality mainly in adults aged 45 and over.

This lack of consistency means a straightforward forecast for Australia and New Zealand isn't possible at this stage. The main question for the Southern Hemisphere is which of these differing viral ecologies will establish itself and become the dominant circulating strain in Australia and New Zealand in 2026.

Implications for Aged Care: Cause for Vigilance

"Do we need to be concerned yet?" This is the crucial question, and the answer, based on global data and local expert views, is a subtle one: there is a clear and strong reason for caution, but not for panic.

It is not currently possible to make direct forecasts for the 2026 Australian and New Zealand flu season. Professor Patrick Reading, Director of the WHO Collaborating Centre in Australia, consistently stresses that predicting the severity of the upcoming season is impossible due to factors such as the dominant virus subtype and human behaviour. As winter advances in the NH and case numbers rise, experts will gain a better understanding of circulating strains, enabling more precise forecasts.

However, the most important concern is not just the virus itself, but also the condition of the host population. Australian and New Zealand experts have pointed out a widespread "immunity gap". Because of years of closed borders and public health measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Southern Hemisphere has not had a normal flu season since 2019. This long period of low viral activity means that immunity at the population level has decreased significantly, leaving many in the community, especially younger people, with limited protection from past seasonal infections.

For aged care residents, this "immunity gap" presents a strong case for a possibly severe flu season. Even if the dominant strain that appears is not inherently more virulent, a population with lower immunity could see more infections, hospital admissions, and serious outcomes. The return of international travel, especially from the Northern Hemisphere, might reintroduce various strains, including the high-impact H3N2 from the US. The combination of a severe strain and an immunocompromised population, such as older adults and those with underlying health conditions in your care, significantly raises the level of risk.

The high number of paediatric deaths in the USA, mainly due to Influenza A and with 90% of those children unvaccinated, is a serious warning. While this mainly concerns children, it highlights the severity of circulating influenza A strains and the crucial role of vaccination as the primary prevention measure. The European experience, with excess mortality in adults aged 45 and over, further shows the potential impact on older people. As one Australian expert aptly said, "it's always a bad flu season because it's hospitalising and killing people".

It is not currently possible to make direct forecasts for the 2026 Australian and New Zealand flu season. Professor Patrick Reading, Director of the WHO Collaborating Centre in Australia, consistently stresses that predicting the severity of the upcoming season is impossible due to factors such as the dominant virus subtype and human behaviour. As winter advances in the NH and case numbers rise, experts will gain a better understanding of circulating strains, enabling more precise forecasts.

However, the most important concern is not just the virus itself, but also the condition of the host population. Australian and New Zealand experts have pointed out a widespread "immunity gap". Because of years of closed borders and public health measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Southern Hemisphere has not had a normal flu season since 2019. This long period of low viral activity means that immunity at the population level has decreased significantly, leaving many in the community, especially younger people, with limited protection from past seasonal infections.

For aged care residents, this "immunity gap" presents a strong case for a possibly severe flu season. Even if the dominant strain that appears is not inherently more virulent, a population with lower immunity could see more infections, hospital admissions, and serious outcomes. The return of international travel, especially from the Northern Hemisphere, might reintroduce various strains, including the high-impact H3N2 from the US. The combination of a severe strain and an immunocompromised population, such as older adults and those with underlying health conditions in your care, significantly raises the level of risk.

The high number of paediatric deaths in the USA, mainly due to Influenza A and with 90% of those children unvaccinated, is a serious warning. While this mainly concerns children, it highlights the severity of circulating influenza A strains and the crucial role of vaccination as the primary prevention measure. The European experience, with excess mortality in adults aged 45 and over, further shows the potential impact on older people. As one Australian expert aptly said, "it's always a bad flu season because it's hospitalising and killing people".

Recommendations for Aged Care Preparedness

Based on this analysis, several recommendations are critical for preparing for the 2026 influenza season, with a specific focus on aged care residents:

- Prioritise annual vaccination: Annual influenza vaccination is the most effective way to prevent influenza and its serious complications

- Consider Co-administration and Broader Vaccination Programs: The UK's Winter 2025/26 Vaccination Program emphasises increasing vaccination rates to lessen the burden on urgent care, especially for flu and COVID-19. It highlights eligibility for COVID-19 vaccines for residents in care homes for older adults, all adults aged 75 and over, and immunosuppressed individuals aged 6 months and above. The program aims to align the start dates for adult flu and COVID-19 vaccinations (from 1 October 2025) to facilitate co-administration whenever possible. Regions are specifically encouraged to prioritise vaccinations for residents in older adult care homes and those who are housebound. Healthcare systems are also advised to pay special attention to RSV and other vaccinations, co-administering vaccines where appropriate and safe.

- Address Vaccination Barriers: Ongoing low vaccination rates are concerning, often caused by barriers such as cost, difficulty booking appointments, inconvenient hours, and inability to take time off work. Tackling these through tailored campaigns and improved access, particularly for housebound people via outreach services, is a vital public health goal.

- Reinforce Complementary Preventative Measures: Beyond vaccination, highlight good hand hygiene, focus on air quality and ventilation, and, most importantly, stay home from work or school when feeling unwell. For healthcare personnel, this last point is crucial to prevent onward transmission to vulnerable residents.

While the nasal spray flu vaccine, FluMist, received FDA approval in September 2024 for self- or caregiver administration for individuals aged 2 through 49, this option is expected to be available from the 2025-2026 flu season. While not directly applicable to older adults in your care, it represents an evolving landscape in vaccine delivery.

Conclusion

The 2026 flu season in Australia and New Zealand poses an increased risk of impact, influenced by the severe and varied Northern Hemisphere season and our own population's "immunity gap." For aged care and housebound individuals, this requires our full attention. Vigilance, proactive vaccination – particularly with enhanced vaccines for older adults – and strengthening comprehensive preventative measures are our best defences against a potentially tough season. Your role in enacting these strategies will be vital in safeguarding your residents.

Food for thought? Explore this and other topics by visiting the IPS HUB or talking to EVE in your own language!

To speak to our friendly team, contact support@infectionprevention.care

We are on Facebook and LinkedIn – don’t forget to like and share.

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

Food for thought? Explore this and other topics by visiting the IPS HUB or talking to EVE in your own language!

To speak to our friendly team, contact support@infectionprevention.care

We are on Facebook and LinkedIn – don’t forget to like and share.

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

Lyndon Forrest

Managing Director | CEO

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

Erica Callaghan

Marketing Manager

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Toni Sherriff

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Julie Hadfield

Accounts & Payroll

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Andrea Murray

Content Editor

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

Personally, I lived in the UK for 10 years. My two children were born in Scotland, and now both are living in Europe, one in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. I live close to Fairlie on the South Island of NZ, a beautiful part of the country, and I love being out of the city.

Princess

Customer Support

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Dianne Newey

Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

In my role, I promote Infection Prevention and Control, to RACF's and disability support services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

Caoimhe (Keva) Stewart

Clinical & Business Operations Manager

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Her move from nursing to customer service was driven by her passion for helping others, not just in clinical settings but also in ensuring that people have access to the resources and support they need. Now, Caoimhe applies her problem-solving skills, attention to detail, and communication expertise to her role, helping to create a positive and effective learning environment for all students.

Outside of work, Caoimhe enjoys travelling, staying active, and catching up with friends on the weekends. Whether in healthcare or customer service, she’s dedicated to making a meaningful difference and supporting people in their personal and professional growth.

Bridgette Mackie

Clinical Nurse Educator

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.