Jul 6

Legionnaires' Disease and the Older Person

A Critical Concern in Aged Care

Legionnaires' disease, a severe form of pneumonia caused by Legionella bacteria, poses a significant threat, particularly to older individuals in aged care facilities. Although this bacterial infection is not transmitted person-to-person, it must be taken seriously. It can become a critical illness in the most vulnerable, often leading to hospitalisation and even death. Understanding the disease process and its prevention, particularly in aged care residences, is paramount.

Understanding Legionnaires' Disease

Legionnaires' disease is caused by Legionella bacteria, naturally found in freshwater environments such as lakes and streams. However, these bacteria become a health concern when they grow and spread in man-made water systems. These include:

- Showerheads and sink taps

- Hot tubs and spa pools

- Decorative fountains and water features

- Large, complex plumbing systems

- Cooling towers (often used in air conditioning for large buildings)

- Humidifiers and ice machines

People can contract Legionnaires' disease by inhaling small droplets of contaminated water as an aerosol, containing the bacteria. In some rarer cases, especially in Australia and New Zealand, exposure to contaminated soil or potting mix can also lead to infection from Legionella longbeachae.

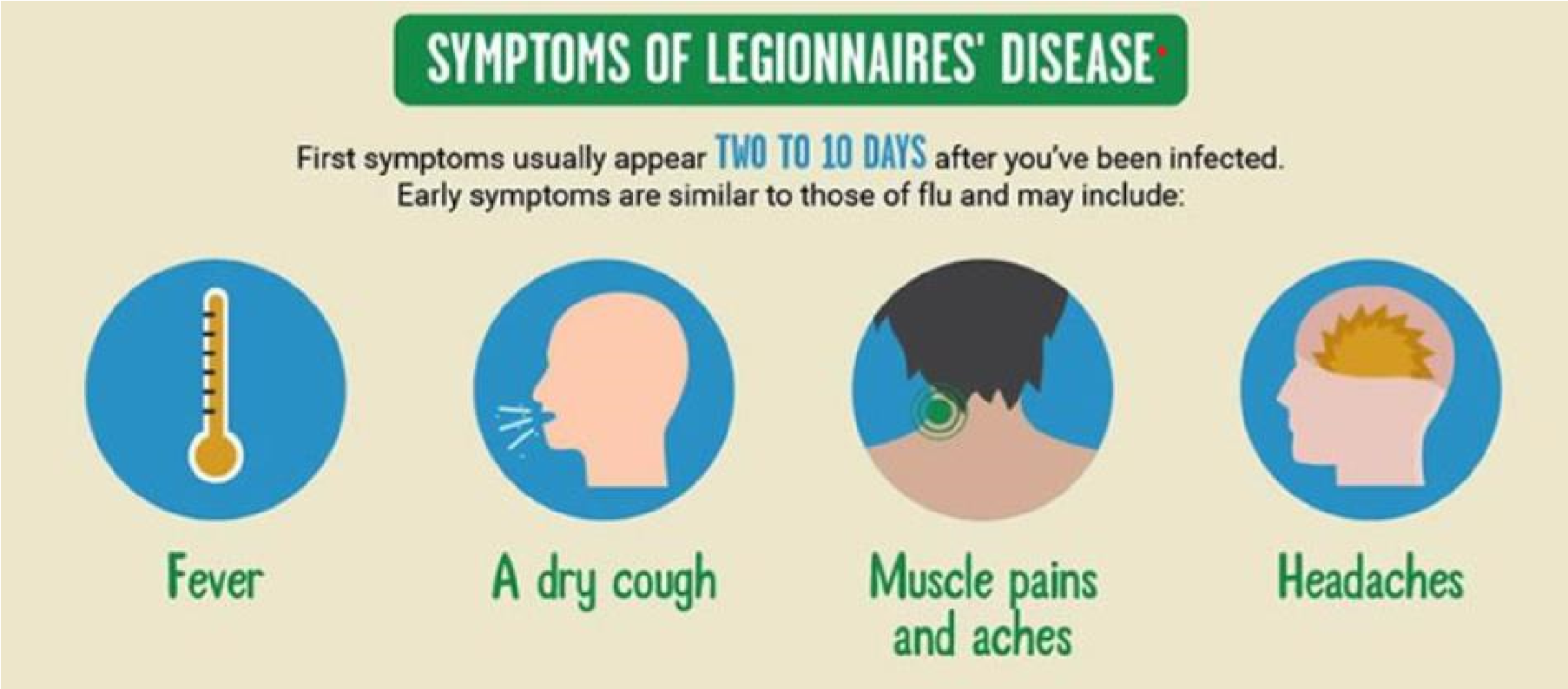

Symptoms typically develop 2 to 10 days after exposure and can resemble the flu initially, including:

- Fever (often high, 40°C or higher)

- Chills

- Cough (which may produce mucus or blood)

- Muscle aches

- Headaches

As the disease progresses, more severe symptoms can emerge:

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea

- Confusion or other mental changes

While most healthy individuals exposed to Legionella don't fall ill, the disease can be very severe, requiring hospitalisation and sometimes intensive care. Possible complications include lung failure, septic shock, and acute kidney failure. Untreated, Legionnaires' disease can be fatal.

History of the Disease: A Philadelphia Mystery

Before its official identification, Legionella bacteria likely caused scattered cases of pneumonia that went undiagnosed. However, the disease gained its name and scientific recognition after an outbreak in July 1976 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

During the annual convention of the American Legion, many attendees, primarily war veterans, fell ill with a severe form of pneumonia. The outbreak caused widespread alarm, with 182 people becoming ill and 29 fatalities. Public health officials, including the Centres for Disease Control (CDC), launched an intensive investigation to identify the cause.

It took several months of dedicated research, with microbiologist Joseph McDade at the CDC playing a pivotal role. Initial attempts to isolate the likely pathogen were unsuccessful, leading researchers to initially suspect a viral agent was the cause. However, McDade's persistent efforts, including experimenting with different culture methods and recognising the need to omit antibiotics from his samples (which were inadvertently killing the bacteria), finally led to the isolation of a previously unknown bacterium in January 1977. This new bacterium was named Legionella pneumophila, in honour of the Legionnaires it afflicted.

Further investigations retrospectively linked Legionella to earlier, unexplained outbreaks of pneumonia, including one in a Washington D.C. hospital in 1965 and a milder illness known as "Pontiac Fever" in Pontiac, Michigan, in 1968. The Philadelphia outbreak served as the turning point, leading to the identification of the bacterium and the subsequent understanding of its prevalence in man-made water systems.

During the annual convention of the American Legion, many attendees, primarily war veterans, fell ill with a severe form of pneumonia. The outbreak caused widespread alarm, with 182 people becoming ill and 29 fatalities. Public health officials, including the Centres for Disease Control (CDC), launched an intensive investigation to identify the cause.

It took several months of dedicated research, with microbiologist Joseph McDade at the CDC playing a pivotal role. Initial attempts to isolate the likely pathogen were unsuccessful, leading researchers to initially suspect a viral agent was the cause. However, McDade's persistent efforts, including experimenting with different culture methods and recognising the need to omit antibiotics from his samples (which were inadvertently killing the bacteria), finally led to the isolation of a previously unknown bacterium in January 1977. This new bacterium was named Legionella pneumophila, in honour of the Legionnaires it afflicted.

Further investigations retrospectively linked Legionella to earlier, unexplained outbreaks of pneumonia, including one in a Washington D.C. hospital in 1965 and a milder illness known as "Pontiac Fever" in Pontiac, Michigan, in 1968. The Philadelphia outbreak served as the turning point, leading to the identification of the bacterium and the subsequent understanding of its prevalence in man-made water systems.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Prompt attention to clinical presentation is key; Legionnaires' disease should be considered in any patient presenting with pneumonia, especially those with certain risk factors like recent travel, healthcare exposure, or failure of outpatient antibiotic therapy. It is crucial to consider Legionella when assessing a community-acquired pneumonia case.

1. Diagnostic Testing

1. Diagnostic Testing

- Urine Antigen Test (UAT): This is a highly specific and rapid test for Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1, which causes most cases. It has a sensitivity of 70- 100% and is positive early in the illness. However, it only detects L. pneumophila serogroup 1 and no other Legionella species or serogroups.

- Culture: Lower respiratory secretions (e.g., sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage) should be cultured on selective media for Legionella. Culture is the most sensitive test for all Legionella species and serogroups and allows for strain typing for epidemiological investigations.

- Molecular Tests (PCR): Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are increasingly available and can detect Legionella DNA from respiratory specimens, offering higher sensitivity than culture in some cases.

- Direct Fluorescent Antibody (DFA) Staining: While rapid, DFA staining of respiratory specimens is less sensitive and specific than culture or NAAT and is generally not recommended as a primary diagnostic method.

- Serology: Paired serum samples (acute and convalescent) showing a fourfold or greater rise in antibody titre against Legionella can indicate infection, but results take weeks and are not useful for acute management.

2. Treatment:

- Antibiotics are Essential: Legionnaires' disease must be treated with antibiotics. Treatment should be initiated promptly based on clinical presentation and history, even before laboratory confirmation, due to the severity of the illness. Prompt initiation of treatment also improves outcomes and prevents serious complications.

- Recommended Antibiotics: Fluoroquinolones (e.g., levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, ciprofloxacin) are generally the preferred first-line agents due to their excellent intracellular penetration and clinical efficacy. Macrolides (e.g., azithromycin) are also effective, especially in less severe cases, but resistance can occur.

- Duration of Treatment: The duration of antibiotic therapy typically ranges from 7-10 days but may be extended to 2-3 weeks in immunocompromised patients or those with severe disease.

- Lack of Person-to-Person Spread: Since the disease is not transmitted from

person to person, contact tracing and prophylaxis for contacts are not

necessary.

3. Hospitalisation: Most individuals with Legionnaires' disease, especially older persons and those with underlying health conditions, require hospitalisation for treatment and close monitoring. Supportive care is essential and may include:

- Oxygen therapy: To assist with breathing difficulties.

- Intravenous fluids: To prevent dehydration.

- Mechanical ventilation: In severe cases where respiratory failure occurs, ventilation may be required to assist breathing.

- Management of complications: To address any complications if they arise, such as kidney failure (e.g., dialysis) or septic shock.

It's important to note that a milder form of the infection, known as Pontiac fever, caused by the same bacteria, typically resolves on its own without antibiotic treatment. However, because the initial symptoms can be similar, anyone suspected of having Legionnaires' disease should seek prompt medical attention for correct diagnosis and treatment.

Increased Risk for Older Persons

Older adults are disproportionately affected by Legionnaires' disease. Individuals aged 50 and above are at a significantly higher risk of contracting the illness and experiencing more severe outcomes. This vulnerability is compounded by several factors common in the older population:

- Weakened Immune Systems: As people age, their immune systems naturally become less robust, making them more susceptible to infections.

- Chronic Health Conditions: Many older adults live with chronic illnesses such as chronic lung disease (e.g., COPD, emphysema), diabetes, kidney failure, heart disease, or cancer. These conditions further compromise their ability to fight off infection.

- Smoking History: Current or former smokers have damaged lungs, increasing the risk of all types of lung infections, including Legionnaires' disease.

- Underlying Medications: Certain medications, such as steroids or those medications taken after organ transplantation, can suppress the immune system, increasing susceptibility.

Impact in Aged Care Residences

Aged care residences present a unique environment where the risk and impact of Legionnaires' disease can be particularly pronounced. The concentration of vulnerable individuals, coupled with potentially complex water systems, creates a heightened need for stringent preventative measures.

- Vulnerable Population: Aged care facilities house a high percentage of individuals with multiple risk factors, making them highly susceptible to severe illness and higher mortality rates if an outbreak occurs.

- Complex Water Systems: Large buildings, including aged care facilities, often have extensive plumbing systems, hot water systems, and potentially, cooling towers. These water systems can become breeding grounds for Legionella if not properly maintained. Areas of water stagnation (e.g., infrequently used taps, "dead legs" in piping) can also promote bacterial growth.

- Challenges in Diagnosis: The initial flu-like symptoms can be mistaken for other common ailments in older adults. Diagnosis and treatment may be delayed, which can significantly worsen outcomes.

- Increased Morbidity and Mortality: Outbreaks in aged care settings can lead to a higher number of severe cases, prolonged hospital stays, and increased fatalities due to the residents' underlying health co-morbidities.

- Emotional and Reputational Impact: An outbreak can cause significant distress for residents, their families, and staff, and severely damage the reputation of the facility.

Prevention in Aged Care Residences

Preventing Legionnaires' disease in aged care facilities is based on comprehensive water management programs and diligent maintenance.

Key preventive measures include:

Key preventive measures include:

- Water Management Plans: Implementing a robust water management program to identify, track, and improve operation and maintenance activities for all water systems. Adherence to standards is an essential practice in aged care in Australia. Regular maintenance of water systems is mandated with service intervals of not more than 12 months. In some states and territories, serviced by a registered plumber to meet compliance. Legionella testing should be conducted regularly, although the frequency can also vary depending on the risk category of the facility. This risk is dependent on whether the facility has had previous Legionella detection, has complex water systems or has aged and immunocompromised residents. Testing is also required after major plumbing work or disruption of the water supply. Development of a Legionella Management Plan is considered best practice.

- Temperature Control: Maintaining water temperatures outside the favourable growth range for Legionella. Hot water should be stored and circulated at temperatures above 60°C, and cold water below 20°C. However, in healthcare settings, this must be balanced to prevent scalding (often requiring water at outlets to be no more than 45°C). Careful system design is required, and there should potentially be point-of-use thermostatic mixing valves on sinks and showers.

- Preventing Stagnation: Regularly flushing low flow piping runs, "dead legs" (unused sections of pipe), and infrequently used fixtures (like showers and taps) to prevent water stagnation. Auto-drain shower systems and touchless taps are helpful.

- Cleaning and Maintenance: Regularly cleaning and maintaining all water system components, including showerheads, taps, cooling towers, hot water tanks, ice machines, and humidifiers, following the manufacturers’ recommendations.

- Disinfection: Consider the appropriate disinfection methods for water systems, especially in high-risk areas or if Legionella is detected.

- Staff Training: Ensuring all staff involved in water system management and resident care are adequately trained on Legionella risks, prevention, and the recognition of symptoms.

- Prompt Action for Symptoms: Encouraging residents and staff to report any potential symptoms promptly and ensuring prompt medical evaluation and testing if Legionnaires' disease is suspected.

Recent Outbreaks in Sydney, Australia (2024-2025)

Sydney has experienced recent Legionnaires' disease outbreaks, highlighting the ongoing risk of Legionella infections.

Recent events underscore the importance of ongoing vigilance, especially in urban environments with numerous cooling towers and shared water systems. Building owners are legally obligated under the NSW Public Health Regulation 2022 to regularly maintain and test their cooling systems. It is worth noting that Sydney has now changed its water testing protocols to a risk-based approach rather than yearly compliance.

- Potts Point Outbreak (June 2025): NSW Health issued a public warning after three people, aged between their 40s and 70s, were hospitalised with Legionnaires' disease after visiting or living in the Potts Point area. Investigations are underway, with health officials inspecting cooling towers within 500 meters of the residents' homes as the likely source.

- Sydney CBD Outbreak (Earlier 2025): Earlier in 2025, a separate incident in Sydney's CBD infected 12 people and resulted in one death. This outbreak was traced to a cooling tower contaminated with Legionella. It has since been decontaminated.

Recent events underscore the importance of ongoing vigilance, especially in urban environments with numerous cooling towers and shared water systems. Building owners are legally obligated under the NSW Public Health Regulation 2022 to regularly maintain and test their cooling systems. It is worth noting that Sydney has now changed its water testing protocols to a risk-based approach rather than yearly compliance.

Conclusion

Legionnaires' disease poses a serious and preventable threat, particularly to older individuals and those in aged care residences. Understanding the disease's history, recognising risk factors, and implementing robust prevention strategies are vital for safeguarding the health and well-being of this vulnerable population. The availability of effective antibiotic treatments, coupled with proactive measures to manage water systems, offers the best defence against this severe illness. The recent outbreaks in Sydney serve as a reminder of the need for continuous awareness and diligent efforts to mitigate the risks.

If you enjoyed this blog post, others on a variety of topics are available weekly on the HUB.

Follow us on Facebook and LinkedIn. Be sure to like and share!

Any further questions? Ask EVE, our multilingual “bot”, or contact our helpful team at support@infectioncontrol.care

If you enjoyed this blog post, others on a variety of topics are available weekly on the HUB.

Follow us on Facebook and LinkedIn. Be sure to like and share!

Any further questions? Ask EVE, our multilingual “bot”, or contact our helpful team at support@infectioncontrol.care

Lyndon Forrest

Managing Director | CEO

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

Erica Leadley

Manager, Marketing and Sales

Erica Leadley is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Erica Leadley is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Toni Sherriff

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Julie Hadfield

Accounts & Payroll

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Andrea Murray

Content Editor

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

Personally, I lived in the UK for 10 years. My two children were born in Scotland, and now both are living in Europe, one in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. I live close to Fairlie on the South Island of NZ, a beautiful part of the country, and I love being out of the city.

Princess

Customer Support

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Dianne Newey

Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

In my role, I promote Infection Prevention and Control, to RACF's and disability support services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

Caoimhe (Keva) Stewart

Manager of Customer Service

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Her move from nursing to customer service was driven by her passion for helping others, not just in clinical settings but also in ensuring that people have access to the resources and support they need. Now, Caoimhe applies her problem-solving skills, attention to detail, and communication expertise to her role, helping to create a positive and effective learning environment for all students.

Outside of work, Caoimhe enjoys travelling, staying active, and catching up with friends on the weekends. Whether in healthcare or customer service, she’s dedicated to making a meaningful difference and supporting people in their personal and professional growth.