Sep 29

Psychological Care in Aged Care Facilities

Mental Health in Aged Care

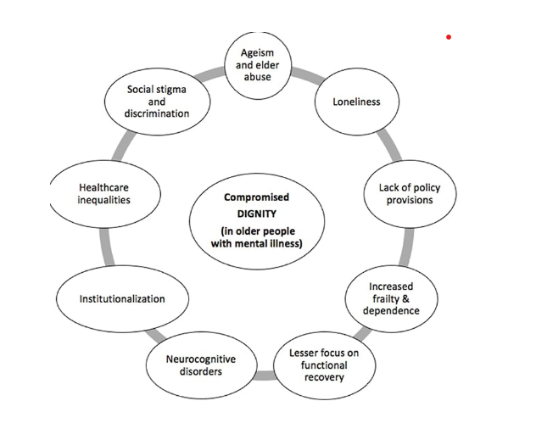

As healthcare professionals committed to the well-being of older adults, we are experts in managing complex physical conditions. However, a silent, widespread issue exists beyond charts and medication schedules—the deep psychological distress experienced by some residents in aged care facilities. Research indicates that between 65% and 91% of residents have a mental disorder. This is not a minor physical health issue; it is a fundamental challenge that influences their entire experience. Conditions like depression and anxiety are often overlooked, with their symptoms mistaken for an inevitable part of aging. This blog will explore the psychological landscape of aged care, uncover the root causes of this distress and offer practical tools for identification, intervention, and fostering a truly supportive environment.

Neglect: Prevalence and Consequences

The mental health of aged care residents is an issue affecting most individuals in our care. While larger studies of older adults show depression as the most common disorder at 17.1%, with panic and anxiety at 11.3%, the prevalence seems to rise with age. Despite these figures, mental health concerns often go untreated, mainly because of the diagnostic challenge of symptomatic overlap. The classic signs of depression-loss of interest, reduced energy, changes in sleep- are often and easily mistaken for signs of ageing or cognitive decline, especially in residents with other conditions such as dementia.

This oversight is not harmless. The effects of untreated mental distress are serious and create a vicious cycle that harms both mind and body. A strong, two-way connection exists between mental and physical health; for example, a resident with heart disease who develops depression may face a worse outlook for their cardiac condition. This neglect can hasten a decline in physical ability, encourage social withdrawal, and ultimately reduce a resident’s quality of life, highlighting the urgent need for a holistic approach to care.

This oversight is not harmless. The effects of untreated mental distress are serious and create a vicious cycle that harms both mind and body. A strong, two-way connection exists between mental and physical health; for example, a resident with heart disease who develops depression may face a worse outlook for their cardiac condition. This neglect can hasten a decline in physical ability, encourage social withdrawal, and ultimately reduce a resident’s quality of life, highlighting the urgent need for a holistic approach to care.

More Than Just a Diagnosis

Beyond formal diagnoses, a resident's emotional world is often shaped by a complex and nuanced landscape of feelings. Understanding these states is essential for delivering compassionate care.

• Disenchantment with Life: This is a widespread sense of losing purpose and interest in activities that once brought joy. It directly results from the shift from an independent, self-directed life to one of dependence. At its heart, disenchantment reflects a deep, underlying grief for a life once familiar, a feeling of "existing rather than living."

• Loneliness vs. Social Isolation: It is essential to distinguish between these two states. A resident can be surrounded by people in a communal setting yet feel deeply lonely. Research confirms this subjective experience, with studies suggesting that about 61% of residents may feel moderately lonely, and nearly 35% are severely so. This occurs because the people around them are "effectively strangers," and the resident has become disconnected from their established social networks of friends, family, and community groups.

• Fear of Health Problems: A specific and rational form of anxiety is often present, rooted in the ongoing reality of physical decline. Residents may develop a significant fear of falling, becoming injured, or seeing their existing health conditions worsen. This is a logical response to a new environment where physical vulnerability is a daily reality.

• Loneliness vs. Social Isolation: It is essential to distinguish between these two states. A resident can be surrounded by people in a communal setting yet feel deeply lonely. Research confirms this subjective experience, with studies suggesting that about 61% of residents may feel moderately lonely, and nearly 35% are severely so. This occurs because the people around them are "effectively strangers," and the resident has become disconnected from their established social networks of friends, family, and community groups.

• Fear of Health Problems: A specific and rational form of anxiety is often present, rooted in the ongoing reality of physical decline. Residents may develop a significant fear of falling, becoming injured, or seeing their existing health conditions worsen. This is a logical response to a new environment where physical vulnerability is a daily reality.

The Root Causes of Psychological Vulnerability

To intervene effectively, we need to first identify the triggers that make residents particularly vulnerable to psychological distress. The distress is not a sudden event but a response to significant life changes.

The Trauma of Transition: Relocation Stress Syndrome (RSS)

The journey into care often begins with a traumatic event: the move itself. This is far more than just a change of address; it can trigger an acute stress disorder called Relocation Stress Syndrome (RSS), or transfer trauma. Marked by intense anxiety, depression, and confusion, RSS can also show physical symptoms like headaches, appetite fluctuations, and sleep issues, usually within the first month after the move. This distress isn't limited by mental capacity; both cognitively impaired and unimpaired residents can experience similar levels of suffering.

A major challenge is that RSS is often seen as an "invisible diagnosis". Its symptoms are so easily mistaken for issues related to ageing or dementia that staff may interpret a new resident's irritability or withdrawal as an unmanageable chronic condition rather than an acute, treatable stress reaction. This lack of institutional awareness means a resident’s distress is often met with an inadequate response, preventing a proactive and compassionate intervention when it is needed most.

A major challenge is that RSS is often seen as an "invisible diagnosis". Its symptoms are so easily mistaken for issues related to ageing or dementia that staff may interpret a new resident's irritability or withdrawal as an unmanageable chronic condition rather than an acute, treatable stress reaction. This lack of institutional awareness means a resident’s distress is often met with an inadequate response, preventing a proactive and compassionate intervention when it is needed most.

The Loneliness Epidemic and Compounding Grief

A resident’s mental vulnerability is driven by a chronic and accumulating sense of loss. The process starts with surrendering their home and reducing a lifetime of possessions to fit in a single room. This is followed by the breakdown of social supports, loss of independence, and declining physical health. It is not a single period of grief but a prolonged state of mourning, worsened by the passing of new friends made within the facility. This ongoing bereavement forms the psychological basis for the disillusionment many residents experience. It emphasises that effective care must be a continuous support process for individuals facing these repeated losses.

The Relationship Between Mind and Body

The link between physical and mental health is especially strong in aged care. Chronic pain is a significant predictor of mental distress. Research indicates that older adults with chronic pain are up to 4.1 times more likely to develop depression, and around 65% of those with depression also report experiencing at least one type of pain. This creates a vicious cycle: pain and mobility issues lead to frustration and withdrawal, which then worsen social isolation and the physical symptoms of pain. A major barrier is the lack of staff training and clear protocols for managing physical and mental health together, leaving many residents' interconnected needs unaddressed.

From Observation to Action

As frontline professionals, our ability to identify the early signs of mental distress is the first line of defence. This requires a proactive and informed approach that combines keen observation with objective tools.

The Role of Observation

The Role of Observation

Care workers who spend the most time with residents are uniquely placed to notice the subtle emotional, behavioural, and physical signs of distress. These signs can include:

- Emotional and Psychological Signs: Feelings of sadness, hopelessness, or helplessness; guilt or self-blame; irritability, agitation, or angry outbursts; and constant worry or unrealistic fears. In severe cases, this may include thoughts of death or suicide.

- Behavioural Indicators: A key sign is social withdrawal or self-isolation, such as a loss of interest in hobbies, reluctance to see family, or sudden apathy. Uncharacteristic negativity or slowed thinking, speaking, or movement are also red flags.

- Physical and Somatic Signs: These can be subtle but are equally important. Watch for a decline in personal hygiene and appearance, changes in appetite or unexplained weight fluctuations, and shifts in sleep patterns, such as insomnia or excessive sleepiness. Unexplained aches, pains, constant fatigue, or a loss of libido also highlight the deep connection between physical and mental health.

Leveraging Validated Screening Tools

While observation is important, it can be subjective. To achieve a more objective and evidence-based assessment, we should utilise validated screening tools, such as the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The GDS is specifically designed for older adults, making it highly relevant. Using these tools offers "quantifiable evidence of a patient’s/resident’s state of health," which helps establish a baseline and objectively track a resident’s progress or decline over time.

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

For a population whose distress is often rooted in situational factors like loss and loneliness, non-pharmacological interventions are the most effective and compassionate first-line treatments. The foundation of this approach is person-centred care, a philosophical shift from a service-based model to one of partnership. This means respecting each resident's unique needs and values, involving them in their care planning, and focusing on what they are still capable of doing to foster dignity and autonomy.

Beyond this philosophy, multiple evidence-based activities can directly enhance well-being.

Beyond this philosophy, multiple evidence-based activities can directly enhance well-being.

- Reminiscence Therapy: Using sensory cues such as old photographs, music, or memorabilia helps residents revisit past experiences, which has been shown to improve mood, increase sociability, and foster a sense of self-worth. This is especially powerful for people with dementia, as it taps into preserved long-term memories.

- Art and Music Therapy: These activities offer a way for residents to express themselves, especially those with advanced cognitive decline. Music can help decrease agitation, while art projects give a sense of achievement and purpose, enabling residents to convey emotions without words.

- Physical Activity: Gentle, regular movement suited to a resident’s abilities—such as walks, yoga, or seated exercises—can significantly ease symptoms of anxiety and depression. Highlighting what a resident can do, instead of what they can't, helps preserve mobility and prevents disillusionment.

- Social Engagement: To directly tackle loneliness, care staff can create opportunities for residents to connect by introducing those with shared interests, facilitating group activities like a book club, and supporting family visits effectively.

Pharmacological Interventions

While non-pharmacological approaches should come first, medication remains an important tool for severe or persistent conditions. Nurses play a critical role in the safe and effective administration of medication. The evidence suggests that the benefits of antidepressants in nursing homes can sometimes be unclear beyond a placebo effect, and they come with risks like increased falls and sleep disturbances.

First-line treatments include Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) such as citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline, as well as Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) like venlafaxine and duloxetine. These are generally well-tolerated and carry a lower risk of drug interactions, which is particularly important in the elderly with polypharmacy. SNRIs are also effective for residents with co-occurring chronic pain. Conversely, some medications should usually be avoided, including tricyclic antidepressants (because of high risk of confusion and sedation) and benzodiazepines (due to risks of addiction, falls, and mortality).

A nurse's role involves proactive vigilance. A medication regimen must always "start low and go slow" because of the slower metabolism in older adults. Nurses need to monitor carefully for side effects like gastrointestinal upset or changes in blood pressure and use tools such as pill organisers to prevent missed doses or oversedation.

First-line treatments include Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) such as citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline, as well as Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) like venlafaxine and duloxetine. These are generally well-tolerated and carry a lower risk of drug interactions, which is particularly important in the elderly with polypharmacy. SNRIs are also effective for residents with co-occurring chronic pain. Conversely, some medications should usually be avoided, including tricyclic antidepressants (because of high risk of confusion and sedation) and benzodiazepines (due to risks of addiction, falls, and mortality).

A nurse's role involves proactive vigilance. A medication regimen must always "start low and go slow" because of the slower metabolism in older adults. Nurses need to monitor carefully for side effects like gastrointestinal upset or changes in blood pressure and use tools such as pill organisers to prevent missed doses or oversedation.

Building a Culture of Support for a Sustainable Solution

Isolated interventions are insufficient. Achieving sustainable change requires a systemic commitment from the entire facility, starting with frontline staff.

Nurse aides and certified nursing assistants provide up to 90% of direct patient care, yet they often have the least amount of mental health training. This systemic flaw leads to staff frustration, burnout, and an alarmingly high turnover rate; up to 129% in some studies. This constant staff turnover has a harmful impact on residents, who are surrounded by a revolving door of "strangers," undermining stability and worsening their feelings of loneliness.

Families are also vital partners, offering essential emotional support, companionship, and advocacy. They can provide a deep understanding of a resident's personal history, which is crucial for creating a truly person-centred care plan.

Ultimately, the responsibility for creating a psychologically healthy environment lies with facility leadership. They must foster a compassionate culture that destigmatises mental health, ensures access to mental health professionals, and provides ongoing staff training. Models like the Eden Alternative, which address boredom, loneliness, and helplessness by prioritising meaningful activities and relationships, offer a strong framework for change.

Nurse aides and certified nursing assistants provide up to 90% of direct patient care, yet they often have the least amount of mental health training. This systemic flaw leads to staff frustration, burnout, and an alarmingly high turnover rate; up to 129% in some studies. This constant staff turnover has a harmful impact on residents, who are surrounded by a revolving door of "strangers," undermining stability and worsening their feelings of loneliness.

Families are also vital partners, offering essential emotional support, companionship, and advocacy. They can provide a deep understanding of a resident's personal history, which is crucial for creating a truly person-centred care plan.

Ultimately, the responsibility for creating a psychologically healthy environment lies with facility leadership. They must foster a compassionate culture that destigmatises mental health, ensures access to mental health professionals, and provides ongoing staff training. Models like the Eden Alternative, which address boredom, loneliness, and helplessness by prioritising meaningful activities and relationships, offer a strong framework for change.

Our Next Step? A Call to Action

The mental health crisis in aged care is significant, often overlooked, and rooted in trauma, loss, and systemic issues. Tackling it requires a dedicated, multifaceted approach that aims beyond mere survival to genuinely support residents to thrive. Here are our next steps:

1. For ourselves: as professionals, we must look for subtle signs of distress, combining vigilant observation with validated screening tools like the GDS. We need to embrace the power of purpose by practising person-centred care and implementing therapeutic activities that restore a sense of autonomy and self-worth. It is crucial to recognise traumatic triggers such as Relocation Stress Syndrome and the compounded grief that shapes a resident's experience. Lastly, for nurses, we must continue to use medication judiciously, with informed vigilance and a holistic perspective.

2. For Our Teams and Facilities: We must advocate for the well-being of our teams. A resilient, well-trained, and stable care team is the most effective intervention for a resident's mental health. Investing in comprehensive mental health training and support for staff is not a luxury; it is a core strategy for improving resident outcomes. By championing these changes, we can transform our facilities from mere places of existence into vibrant communities where every resident feels seen, valued, and psychologically supported.

1. For ourselves: as professionals, we must look for subtle signs of distress, combining vigilant observation with validated screening tools like the GDS. We need to embrace the power of purpose by practising person-centred care and implementing therapeutic activities that restore a sense of autonomy and self-worth. It is crucial to recognise traumatic triggers such as Relocation Stress Syndrome and the compounded grief that shapes a resident's experience. Lastly, for nurses, we must continue to use medication judiciously, with informed vigilance and a holistic perspective.

2. For Our Teams and Facilities: We must advocate for the well-being of our teams. A resilient, well-trained, and stable care team is the most effective intervention for a resident's mental health. Investing in comprehensive mental health training and support for staff is not a luxury; it is a core strategy for improving resident outcomes. By championing these changes, we can transform our facilities from mere places of existence into vibrant communities where every resident feels seen, valued, and psychologically supported.

Visit the HUB for information from our many sources. Alternatively, call our friendly team at support@infectionprevention.care

We are on Facebook and LinkedIn – follow us, like and share

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

We are on Facebook and LinkedIn – follow us, like and share

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

Lyndon Forrest

Managing Director | CEO

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

Erica Callaghan

Marketing Manager

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Toni Sherriff

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Julie Hadfield

Accounts & Payroll

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Andrea Murray

Content Editor

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

Personally, I lived in the UK for 10 years. My two children were born in Scotland, and now both are living in Europe, one in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. I live close to Fairlie on the South Island of NZ, a beautiful part of the country, and I love being out of the city.

Princess

Customer Support

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Dianne Newey

Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

In my role, I promote Infection Prevention and Control, to RACF's and disability support services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

Caoimhe (Keva) Stewart

Clinical & Business Operations Manager

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Her move from nursing to customer service was driven by her passion for helping others, not just in clinical settings but also in ensuring that people have access to the resources and support they need. Now, Caoimhe applies her problem-solving skills, attention to detail, and communication expertise to her role, helping to create a positive and effective learning environment for all students.

Outside of work, Caoimhe enjoys travelling, staying active, and catching up with friends on the weekends. Whether in healthcare or customer service, she’s dedicated to making a meaningful difference and supporting people in their personal and professional growth.

Bridgette Mackie

Clinical Nurse Educator

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.