Oct 18

Aged Care Challenges in Australasia

The aged care sector across Australasia is currently facing an urgent crisis that demands systemic reform and puts enormous operational pressure on frontline healthcare workers. For too long, the system has battled under the burden of inadequate funding and ongoing workforce shortages—issues that have directly contributed to a decline in the quality of care for our most vulnerable older residents.

In both Australia and New Zealand, major government reforms are underway, not just to patch gaps but to fundamentally change the sector's foundation. These changes, driven in Australia by the findings of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, aim to shift from a system focused on providers and funding flows towards one that is rights-based and prioritises the older person's choices and safety. This period of reform is vital, as it represents a necessity to make aged care an attractive, skilled, and sustainable career path. It aims to meet the growing demands of an ageing population while finally ensuring equity and excellence in service delivery.

In both Australia and New Zealand, major government reforms are underway, not just to patch gaps but to fundamentally change the sector's foundation. These changes, driven in Australia by the findings of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, aim to shift from a system focused on providers and funding flows towards one that is rights-based and prioritises the older person's choices and safety. This period of reform is vital, as it represents a necessity to make aged care an attractive, skilled, and sustainable career path. It aims to meet the growing demands of an ageing population while finally ensuring equity and excellence in service delivery.

For healthcare workers in Aged Residential Care (ARC) or Home and Community Support Services (HCSS), understanding the key drivers of this crisis—and the details of the new regulations meant to address them—is essential for managing this transition and meeting the higher standards of care that the public and government now expect. The challenges are complex, involving issues like attracting and retaining staff, developing sustainable financial models, and the crucial integration of technology and cultural safety into daily practice.

Workforce Crisis and Compromised Quality

The most evident pressure on the aged care sector is the serious and urgent workforce crisis. This crisis directly affects how well facilities and services can provide high-quality care, a problem highlighted by systemic reviews.

The Cycle of Shortages

The core issue is the ongoing struggle to recruit new, often younger, talent into the sector, along with the failure to retain experienced, skilled staff. This high turnover and supply shortage stem from deep-seated structural problems: low pay and limited incentives compared to similar sectors like disability services. This is combined with poor career progression, high burnout rates, and widespread job dissatisfaction. For those already in the workforce, the physical and emotional toll is substantial, yet the sector has historically been undervalued.

The data highlights the seriousness of this issue: in Australia, the workforce is expected to face a significant shortfall, with one estimate predicting the sector will lack over 110,000 workers by 2030. Additionally, the workforce itself is aging, with the median age for direct care workers often in the high 40s to early 50s, creating an urgent need for more new professionals. Providers are competing fiercely for skilled staff, dealing with high turnover, and facing a limited pipeline of new recruits. This situation is worsened by job insecurity, often due to part-time or casual work being the norm, and sometimes by a lack of supportive work culture or poor management skills.

The data highlights the seriousness of this issue: in Australia, the workforce is expected to face a significant shortfall, with one estimate predicting the sector will lack over 110,000 workers by 2030. Additionally, the workforce itself is aging, with the median age for direct care workers often in the high 40s to early 50s, creating an urgent need for more new professionals. Providers are competing fiercely for skilled staff, dealing with high turnover, and facing a limited pipeline of new recruits. This situation is worsened by job insecurity, often due to part-time or casual work being the norm, and sometimes by a lack of supportive work culture or poor management skills.

Direct Impact on Care Outcomes

The persistent nature of these workforce shortages directly affects the quality of care. When facilities are understaffed, they often struggle to meet evidence-based quality indicators in key areas. These include:

- Skin integrity and wound management.

- End-of-life care.

- Infection prevention protocols.

- Medication management adherence.

- Mental health care, especially in managing depression.

Insufficient staffing directly results in fewer ‘care minutes’, meaning less time staff can spend with residents. This lack of capacity is closely connected to poorer outcomes for older people, including higher rates of preventable diseases and slower responses to the complex health needs typical of an ageing population.

Adding to the complexity is the significant issue of geographic disparity. Access to skilled workers is highly challenging in regional and remote areas of both Australia and New Zealand, severely hindering service delivery for older people living outside major urban centres.

Adding to the complexity is the significant issue of geographic disparity. Access to skilled workers is highly challenging in regional and remote areas of both Australia and New Zealand, severely hindering service delivery for older people living outside major urban centres.

Funding Models and Financial Viability

The quality crisis cannot be solved without ensuring the sector's financial viability, which is currently under significant pressure. Despite substantial government investments - for example, Australia allocated AUD $24.8 billion in 2021–22 - the sector still faces challenges due to deep-seated structural issues.

Addressing Funding Shortfalls

The number of older Australians, especially those over 80, is rapidly increasing, but government funding has consistently fallen short of this growing need for quality care. In New Zealand, the financial crisis is clear, with a government review now examining the urgent issue of under-funded Aged Residential Care (ARC) and Home and Community Support Services (HCSS). This underspending has real, negative impacts, such as service providers struggling financially and beds being closed.

Australia's reforms are also directly addressing the funding mechanism. Previous funding models, such as the Aged Care Funding Instrument (ACFI), faced widespread criticism and have now been replaced. The current system demands significant additional funding to effectively meet future needs and successfully deliver the necessary quality improvements.

Australia's reforms are also directly addressing the funding mechanism. Previous funding models, such as the Aged Care Funding Instrument (ACFI), faced widespread criticism and have now been replaced. The current system demands significant additional funding to effectively meet future needs and successfully deliver the necessary quality improvements.

New Financial Architectures and Equity

A key aspect of the Australian reform involves changing the financial system to support provider stability. This includes shifting towards means-tested contributions for daily living expenses for wealthier individuals, while ensuring taxpayer funding continues to cover clinical care for all recipients, regardless of their financial situation.

Central to discussions on financial overhaul is the idea of Intergenerational Equity. New funding models must be carefully crafted to guarantee a sustainable and fair aged care system that maintains a balance between contributions from taxpayers and users for non-clinical services. This strategy ensures that future generations are not burdened with an unsustainable funding load, while current older Australians still receive the care they need.

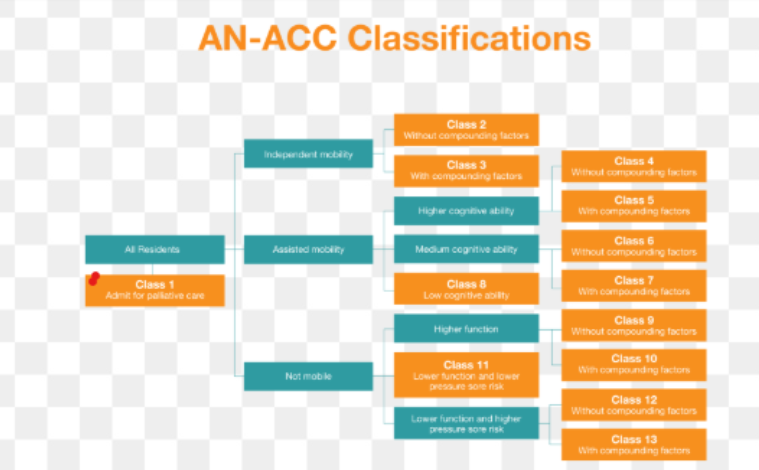

The introduction of the Australian National Aged Care Classification (AN-ACC) funding model in 2022 marks an important milestone in this area. AN-ACC replaced the previous ACFI system and aims to be a fairer funding method for residential aged care, better aligning financial support with the specific, individual care needs of residents.

Central to discussions on financial overhaul is the idea of Intergenerational Equity. New funding models must be carefully crafted to guarantee a sustainable and fair aged care system that maintains a balance between contributions from taxpayers and users for non-clinical services. This strategy ensures that future generations are not burdened with an unsustainable funding load, while current older Australians still receive the care they need.

The introduction of the Australian National Aged Care Classification (AN-ACC) funding model in 2022 marks an important milestone in this area. AN-ACC replaced the previous ACFI system and aims to be a fairer funding method for residential aged care, better aligning financial support with the specific, individual care needs of residents.

Reform, Rights, and Accountability

Both Australia and New Zealand are implementing sector-wide government reforms

aimed at significantly enhancing the quality, safety, and transparency of aged care.

These reforms necessitate a fundamental change in the philosophy and operational

practices of healthcare personnel.

A Change to Person-Centred Care

A Change to Person-Centred Care

Perhaps the most notable change is the shift towards Person-Centred Care. This

approach is being formally embedded in Australia's new Aged Care Act, which is set to

come into effect on 01 November 2025. The legislation creates a rights-based

framework for care, fundamentally redirecting the system's focus away from providers

and funding sources, ensuring that the rights and preferences of older individuals are at

the heart of all decisions. Meanwhile, New Zealand is also actively considering adopting

a similar approach.

For healthcare workers, this signifies a renewed commitment to transparency,

communication, and responding to individual needs, going beyond mere compliance to

truly empowering older persons.

Mandatory Staffing and Safety

Mandatory Staffing and Safety

To address the immediate quality concerns linked to shortages, Australia has

introduced strict, actionable mandates for residential care providers.

1. Mandatory Care Minutes: Residential aged care homes are now required to meet specific targets for the minimum amount of time residents receive direct care from both nursing staff and personal care staff. This is a clear effort to ensure residents get the attention they need.

2. 24/7 Registered Nurse (RN) Coverage: Since July 2023, residential homes have been required to have a Registered Nurse on-site and on duty 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, although some specific exemptions do apply. This guarantees that clinical oversight is always accessible.

Furthermore, accountability and safety standards are being significantly strengthened. The Serious Incident Response Scheme (SIRS), originally limited to residential care, has now been expanded to cover home care. This change offers greater protection for older Australians from abuse and neglect across all care settings.

Enhancing Governance and Transparency

1. Mandatory Care Minutes: Residential aged care homes are now required to meet specific targets for the minimum amount of time residents receive direct care from both nursing staff and personal care staff. This is a clear effort to ensure residents get the attention they need.

2. 24/7 Registered Nurse (RN) Coverage: Since July 2023, residential homes have been required to have a Registered Nurse on-site and on duty 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, although some specific exemptions do apply. This guarantees that clinical oversight is always accessible.

Furthermore, accountability and safety standards are being significantly strengthened. The Serious Incident Response Scheme (SIRS), originally limited to residential care, has now been expanded to cover home care. This change offers greater protection for older Australians from abuse and neglect across all care settings.

Enhancing Governance and Transparency

New reforms also bolster provider governance and require transparency. These

initiatives impose new responsibilities on providers, including:

These measures collectively aim for higher quality standards, clearer workforce responsibilities, and stronger regulatory oversight to ensure a consistently improved standard of care.

- Mandatory membership of the governance body.

- Establish specific consumer and clinical advisory groups to ensure that the voices of those receiving and delivering care are formally included in decision-making processes.

These measures collectively aim for higher quality standards, clearer workforce responsibilities, and stronger regulatory oversight to ensure a consistently improved standard of care.

Investment in People, Equity, and Innovation

The reform effort recognises that sustainable quality depends not only on new laws and

funding models but also critically on transforming the aged care profession itself and

harnessing modern resources.

Redefining Aged Care as a Skilled Profession

The future of work in aged care requires enhanced training, significantly better working

conditions, and clearer professional development pathways to successfully reshape

the sector as an appealing and skilled career option.

Strategies for attracting and retaining the workforce are complex and require essential government backing.

1. Compensation and Conditions: Government funding now supports significant award wage increases for aged care workers, recognising their value and aiming to boost recruitment and retention. This includes improving pay and working conditions, offering competitive compensation, and appealing benefits to address the longstanding issue of low pay.

2. Professional Development: Enhancing education and training is essential, particularly in specialised fields like palliative and dementia care. Providers should focus on establishing clear career pathways and providing standardised management training to support staff effectively.

3. Work Environment: Building a positive work culture that is respectful, supportive, and inclusive is essential. This involves promoting a supportive leadership style defined by open communication and empathy.

4. Flexibility and Support: Promoting work-life balance is a key retention strategy, achieved through flexible rostering, part-time schedules, and job sharing. Providing on shift support and easy access to necessary information and management resources is equally important.

5. Recognition: Staff must feel valued. This involves acknowledging and rewarding

Strategies for attracting and retaining the workforce are complex and require essential government backing.

1. Compensation and Conditions: Government funding now supports significant award wage increases for aged care workers, recognising their value and aiming to boost recruitment and retention. This includes improving pay and working conditions, offering competitive compensation, and appealing benefits to address the longstanding issue of low pay.

2. Professional Development: Enhancing education and training is essential, particularly in specialised fields like palliative and dementia care. Providers should focus on establishing clear career pathways and providing standardised management training to support staff effectively.

3. Work Environment: Building a positive work culture that is respectful, supportive, and inclusive is essential. This involves promoting a supportive leadership style defined by open communication and empathy.

4. Flexibility and Support: Promoting work-life balance is a key retention strategy, achieved through flexible rostering, part-time schedules, and job sharing. Providing on shift support and easy access to necessary information and management resources is equally important.

5. Recognition: Staff must feel valued. This involves acknowledging and rewarding

employees' efforts with praise, commendations, and bonuses.

Equity and Cultural Safety

A key part of quality reform is the required emphasis on Cultural Safety and Equity. Both

nations must tackle significant material ethnic inequities in accessing aged care. This

focus is especially important for:

Healthcare staff must be trained and adequately equipped to provide culturally appropriate and safe services, ensuring fair access for all citizens.

- Māori and Pasifika older people in New Zealand.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) older individuals in Australia.

Healthcare staff must be trained and adequately equipped to provide culturally appropriate and safe services, ensuring fair access for all citizens.

Technology and Bridging the Digital Divide

As client expectations increase and the population ages, technology provides a

significant opportunity to enhance care quality and efficiency.

The push for Digital Transformation involves leveraging data analytics, IoT (Internet of Things) devices, telehealth services, and comprehensive digital records. These tools are essential for improving efficiency, enhancing monitoring capabilities, and providing robust clinical decision support for staff. Technology also plays a crucial role in supporting the goal of reablement and independence, enabling older adults to stay at home and within their communities for longer.

The push for Digital Transformation involves leveraging data analytics, IoT (Internet of Things) devices, telehealth services, and comprehensive digital records. These tools are essential for improving efficiency, enhancing monitoring capabilities, and providing robust clinical decision support for staff. Technology also plays a crucial role in supporting the goal of reablement and independence, enabling older adults to stay at home and within their communities for longer.

However, implementing technology presents its own challenges. A key issue is the

Digital Divide. Healthcare facilities must ensure that technology does not

unintentionally exclude older people who are less digitally confident. Additionally, there

is an urgent need for comprehensive digital literacy training for the aged care workforce

to ensure staff can use these new tools effectively and confidently.

Conclusion

The challenges facing the Australasian aged care sector, mainly due to longstanding

workforce shortages and funding problems, have prompted significant government

reform. These efforts include legal changes like Australia’s new rights-based Aged Care

Act, practical measures such as Mandatory Care Minutes, and notable wage boosts.

Collectively, they demonstrate a commitment to delivering better care. By

professionalising the workforce, ensuring financial sustainability through models like

AN-ACC, emphasising cultural safety, and adopting technology wisely, the sector aims

for a more consumer-focused, transparent, and high-quality future. The success of this

major shift relies heavily on the dedication and adaptability of healthcare workers who

implement these changes daily.

Follow our regular blogs, all available on the HUB, the IPS website.

We are on Facebook and LinkedIn – like us, follow and share.

For any IPS enquiries, contact our team at support@infectionprevention.care

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

We are on Facebook and LinkedIn – like us, follow and share.

For any IPS enquiries, contact our team at support@infectionprevention.care

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

Lyndon Forrest

Managing Director | CEO

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

Erica Callaghan

Marketing Manager

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Toni Sherriff

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Julie Hadfield

Accounts & Payroll

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Andrea Murray

Content Editor

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

Personally, I lived in the UK for 10 years. My two children were born in Scotland, and now both are living in Europe, one in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. I live close to Fairlie on the South Island of NZ, a beautiful part of the country, and I love being out of the city.

Princess

Customer Support

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Dianne Newey

Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

In my role, I promote Infection Prevention and Control, to RACF's and disability support services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

Caoimhe (Keva) Stewart

Clinical & Business Operations Manager

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Her move from nursing to customer service was driven by her passion for helping others, not just in clinical settings but also in ensuring that people have access to the resources and support they need. Now, Caoimhe applies her problem-solving skills, attention to detail, and communication expertise to her role, helping to create a positive and effective learning environment for all students.

Outside of work, Caoimhe enjoys travelling, staying active, and catching up with friends on the weekends. Whether in healthcare or customer service, she’s dedicated to making a meaningful difference and supporting people in their personal and professional growth.

Bridgette Mackie

Clinical Nurse Educator

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.