Oct 22

Hydration and UTI Management

Introduction

As we enter summer, reports of UTIs increase. Hydration is a crucial factor that should

not be overlooked. This blog focuses on optimising hydration and managing urinary tract

infections (UTIs), particularly in aged care settings in Australia and New Zealand,

especially during warmer months. The text emphasises that dehydration is a significant

risk factor for UTIs and other serious health issues like delirium and heatstroke in older

adults. To address this, there are innovative, structured strategies to encourage

residents to meet their daily fluid targets, such as scheduling regular rounds and

incorporating fluid-rich foods. Importantly, the current national guidelines strongly

discourage the routine use of urine dipstick tests to diagnose UTIs, as these often result

in unnecessary antibiotic treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria (ASB). Instead, best

practice suggests focusing on aggressive hydration, pain relief, and diagnosing UTIs

based solely on the presence of new or worsening clinical urinary symptoms.

We review best practice guidelines from Australia and New Zealand, highlighting innovative hydration approaches, the important shift away from outdated diagnostic tests, and effective non-antibiotic methods for managing UTIs. By implementing these evidence-based practices, we can enhance resident outcomes, minimise unnecessary antibiotic use, and promote antimicrobial stewardship.

We review best practice guidelines from Australia and New Zealand, highlighting innovative hydration approaches, the important shift away from outdated diagnostic tests, and effective non-antibiotic methods for managing UTIs. By implementing these evidence-based practices, we can enhance resident outcomes, minimise unnecessary antibiotic use, and promote antimicrobial stewardship.

Part 1: Mastering Resident Hydration

Hydration is essential for a healthy mind and body. For older adults, maintaining enough

f

luid intake is not just about comfort; it is vital in preventing a range of health issues.

Dehydration can have a serious impact on an older person's health, directly impairing

brain function and leading to critical medical events. Conversely, staying well-hydrated

can boost endurance, lower the heart rate, speed up recovery, and lift mood. Why are

residents in aged care so vulnerable to dehydration?

Adults can lose nearly 2.5 litres of water daily through normal activities, making regular

Adults can lose nearly 2.5 litres of water daily through normal activities, making regular

fluid intake essential. However, several factors specific to older adults render them

especially vulnerable.

- Reduced Thirst Sensation: It’s important to remember that when an older person feels thirsty, their body is already dehydrated. Their natural thirst response is less sensitive.

- Cognitive and Mobility Limitations: Residents with cognitive impairments like dementia may forget to drink, while those with mobility issues might be unable to get a drink themselves.

- Medication Side Effects: Common medications, like diuretics, can lead to increased fluid loss.

- Decreased Appetite and Activity: As appetite and physical activity often decline with age, so can the motivation and routine of drinking fluids.

- Poor Hydration Literacy: A 2017 study found that many older Australians lack

essential knowledge about hydration health literacy. They often overestimate the

amount of fluid loss required to cause symptoms and underestimate the amount of

fluid that needs to be replaced. Additionally, they may not recognise the signs of

dehydration in themselves.

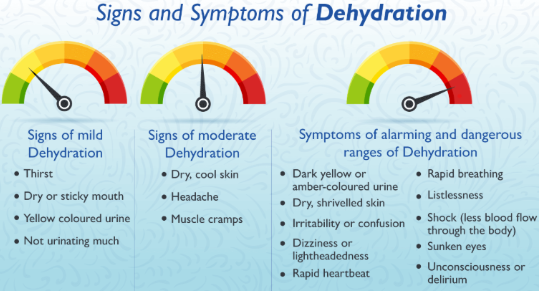

Recognising the Signs: From Mild to Severe

Early identification is essential. Care staff should remain alert for the common signs of

dehydration, which include:

- Fatigue or lethargy

- Muscle weakness and cramps

- Headaches and dizziness

- Nausea

- Forgetfulness and confusion

- Cracked lips and a dry or sticky mouth

- Low urination

- Sunken eyes

If left unchecked, dehydration can cause much more severe medical episodes, such as:

- Psychosis or delirium (dehydration being one of the most common causes of delirium)

- Urinary and kidney problems

- Heat injuries, including heat stroke Seizures

- Seizures

- Low blood volume shock (hypovolemic shock)

- In extreme cases, death

The Challenges of Hydration in Dementia Care

Residents living with dementia face an increased risk of dehydration. Water is crucial for

this group to help prevent behavioural changes, delirium, and depression. However,

specific challenges include:

- Forgetting to drink or even losing the ability to drink.

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), which may lead to choking. A speech pathologist can help address these issues.

- Inability to express thirst or need for help because of loss of mobility or

communication skills

Practical and Creative Hydration Strategies

The aim for most residents is a daily fluid intake of at least 1.5 to 2.0 litres, unless they

are on a fluid restriction prescribed by a doctor. Moving beyond simply asking, "Would

you like a drink?" is essential. Here are evidence-based strategies to reach this target:

1. Make it Routine and Structured:

- Scheduled Hydration Rounds: Conduct rounds every 1.5 to 2 hours throughout the day. Use more assertive, structured prompts, such as "I'd like you to have a drink now."

- Routine Association: Link drinking fluids to other regular events, such as with all

medication rounds, before or after showering, after toileting, and during daily activities.

2. Think Beyond the Water Jug:

- Fluid-Rich Foods: A large part of fluid intake can come from food. Regularly offer high fluid options such as:

◦ Thin custard and yoghurt.

◦ Water-rich fruits and vegetables such as watermelon, cucumber, grapes, tomatoes, spinach and broccoli.

◦ Soups and broths, served at the resident's preferred temperature.

- Offer Variety: To encourage fluid intake, provide alternatives to plain water. This can

include cordials, fruit or vegetable juices, or non-caffeinated teas. Changing the

temperature can also help. While caffeinated drinks and alcohol should be limited as

they can cause dehydration, offering a preferred drink like tea or coffee is better than

letting the resident refuse fluids altogether.

3. Ensure Accessibility and Support

- Personalised Preferences: Find out what each resident truly enjoys drinking and make sure all staff are aware of this.

- Easy Access: Always make sure a drink is within easy reach of the resident.

- Assistive Aids: Use equipment such as extra-long straws, two-handled cups, or other

modified cups to help residents maintain their independence with drinking.

4. Monitor Carefully

- High-Risk Monitoring: For residents at high risk of dehydration (e.g., those with advanced dementia, on diuretics, or with a fever), use and accurately maintain fluid balance charts.

- Addressing Systemic Failures: The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and

Safety has highlighted that some facilities are not managing residents' fluid charts

properly. Meticulous charting is not just paperwork; it is a vital clinical tool for

preventing severe dehydration.

Part 2: A Modern Approach to UTI Diagnosis and Management

Urinary tract infections are a common concern in aged care, but our approach to

diagnosing and treating them must align with current best practices to prevent the

significant harms of over-treatment.

The Verdict on Urine Dipsticks

This marks a crucial change in aged care practice. Clinical pathways at the national and

state levels in Australia and New Zealand strongly advocate against routinely using

urine dipstick tests for suspected UTIs in aged care residents.

The clear message is: Do NOT use a urine dipstick test to diagnose a UTI in an aged care

resident.

Why is this so critical? The reason lies in a condition called Asymptomatic Bacteriuria (ASB).

Why is this so critical? The reason lies in a condition called Asymptomatic Bacteriuria (ASB).

- What is ASB? ASB is the presence of bacteria in the urine without any clinical symptoms of infection. It is a normal, harmless colonisation of bacteria that does not require antibiotic treatment.

- How common is it? ASB is very prevalent among older adults. Up to 50% of older women and a notable number of older men experience it.

- The Dipstick Problem: A positive dipstick result (showing nitrites or leukocyte esterase) cannot differentiate between a genuine, symptomatic UTI and harmless ASB. This often results in the misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment of ASB.

Treating ASB exposes residents to unnecessary antibiotics, increasing their risk of Clostridioides difficile infection and worsening the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) public health crisis. Additionally, treating ASB does not prevent future symptomatic UTIs and often causes more harm than good.

Best Practice: Clinical Assessment is Key

The focus should move from pursuing a positive test result to performing a

comprehensive clinical assessment. A suspected UTI diagnosis must rely on new or

worsening localised urinary symptoms.

Symptoms that may indicate a UTI:

- Cloudy or foul-smelling urine

- Burning or pain during urination (dysuria)

- New or worsening urinary frequency

- New or worsening urinary urgency

- Pain above the pubic bone (suprapubic pain)

- Newly onset incontinence

Symptoms that are NOT sufficient for a UTI diagnosis:

- A shift in behaviour

- A fall

- A general decline in condition

- Cloudy or foul-smelling urine

These vague symptoms are usually caused by other issues, with dehydration being a common cause. Cloudy or foul-smelling urine is most often a sign of dehydration or a reaction to certain foods or medications, not an infection.

Effective Management: Hydration and Non-Antibiotic Strategies First

Before prescribing an antibiotic, especially in mild cases or when symptoms are vague,

concentrate on these important non-pharmacological interventions:

1. Aggressive Hydration: This is the crucial first step. Addressing dehydration can often relieve mild urinary symptoms, such as painful urination (dysuria), and may be the only treatment needed to resolve the resident's condition.

2. Symptom and Pain Relief: Relieve discomfort with simple analgesics like paracetamol (if suitable for the resident). Urinary alkalisers can also help in easing symptoms, although they do not treat the underlying infection.

3. Perineal Hygiene: Practice regular and correct perineal cleaning, especially after toileting and incontinence episodes, to lower the bacterial load locally.

4. Topical Oestrogen: For postmenopausal women experiencing recurrent UTIs, intravaginal oestrogen (available as a cream or pessary) can be highly effective. It works by restoring healthy vaginal flora, which considerably reduces the occurrence of UTIs.

5. Catheter Management: For residents with an indwelling catheter, strict adherence to catheter care bundles is essential. If a UTI is suspected clinically, the catheter should ideally be removed or replaced before collecting a urine sample for culture (MC&S) to prevent contamination.

Conclusion: A Commitment to Better Care

Managing hydration and UTIs effectively in the summer months doesn't have to mean an

automatic spike in antibiotic prescribing. By rigorously prioritising hydration, avoiding

routine dipstick testing, and ensuring all diagnostic decisions are based on strong

clinical assessment and current national guidelines, we can greatly enhance the quality

of life for our residents. This approach not only delivers better, safer care but also

positions our facilities as leaders in antimicrobial stewardship.

Read more of our blogs, available on the HUB, the IPS website.

For individual questions, ask EVE for the answer to a clinical question and receive a

For individual questions, ask EVE for the answer to a clinical question and receive a

reply in your own language! Alternatively, our friendly team are available for enquiries at support@infectionprevention.care

We are on Facebook and LinkedIn. Follow us, like and share

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

We are on Facebook and LinkedIn. Follow us, like and share

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

Lyndon Forrest

Managing Director | CEO

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

Erica Callaghan

Marketing Manager

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Toni Sherriff

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Julie Hadfield

Accounts & Payroll

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Andrea Murray

Content Editor

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

Personally, I lived in the UK for 10 years. My two children were born in Scotland, and now both are living in Europe, one in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. I live close to Fairlie on the South Island of NZ, a beautiful part of the country, and I love being out of the city.

Princess

Customer Support

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Dianne Newey

Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

In my role, I promote Infection Prevention and Control, to RACF's and disability support services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

Caoimhe (Keva) Stewart

Clinical & Business Operations Manager

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Her move from nursing to customer service was driven by her passion for helping others, not just in clinical settings but also in ensuring that people have access to the resources and support they need. Now, Caoimhe applies her problem-solving skills, attention to detail, and communication expertise to her role, helping to create a positive and effective learning environment for all students.

Outside of work, Caoimhe enjoys travelling, staying active, and catching up with friends on the weekends. Whether in healthcare or customer service, she’s dedicated to making a meaningful difference and supporting people in their personal and professional growth.

Bridgette Mackie

Clinical Nurse Educator

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.