Jun 5

The Cost of an Outbreak

Navigating our aged population's often difficult and complex care involves providing compassionate support, ensuring high-quality care, and managing the delicate balance of available resources. However, one significant challenge that can disrupt this balance and impose a substantial financial burden is an infectious disease outbreak in an aged care facility. Understanding not only what constitutes an outbreak but also the many costs associated with such an event is crucial for aged care providers, policymakers, and the wider community. This post aims to shed light on these vital aspects, with insights from available research to explore the definition of an outbreak, the key drivers of its costs, and the essential role and costs of infection prevention and control. It is also important to consider the incorporation of data from the specific region, where possible.

Defining an Outbreak in Aged Care

Before discussing the financial implications, it's essential to understand what an "outbreak" means in the context of an aged care facility. It's more than just a few residents feeling unwell; it signifies a situation requiring a coordinated response and carries specific criteria for identification, often guided by detailed surveillance definitions.

An outbreak occurs when there are more disease cases than usually expected within a specific location and for a target population, such as residents in a long-term care facility. Related is the term "cluster," referring to a group of cases in a place and time that are suspected to be greater than expected, even if the expected number isn't known.

A critical step in effectively investigating an outbreak is the development of a clear case definition, which helps to standardise the identification, consequently, the tracking of cases. A case definition includes specific criteria related to the person, place, time, and clinical features associated with the outbreak. Laboratory criteria may also be included for confirmation of the disease present. Case definitions can be categorised by the degree of diagnostic certainty, such as suspected, probable, or confirmed cases, and may be adjusted as more information becomes available.

An outbreak occurs when there are more disease cases than usually expected within a specific location and for a target population, such as residents in a long-term care facility. Related is the term "cluster," referring to a group of cases in a place and time that are suspected to be greater than expected, even if the expected number isn't known.

A critical step in effectively investigating an outbreak is the development of a clear case definition, which helps to standardise the identification, consequently, the tracking of cases. A case definition includes specific criteria related to the person, place, time, and clinical features associated with the outbreak. Laboratory criteria may also be included for confirmation of the disease present. Case definitions can be categorised by the degree of diagnostic certainty, such as suspected, probable, or confirmed cases, and may be adjusted as more information becomes available.

In aged care settings specifically, the identification of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) that might signal an outbreak or require enhanced surveillance often relies on detailed surveillance definitions for common syndromes, such as the McGeer Criteria (detailed in the previous post). Examples of criteria for various infections include Urinary Tract Infection (UTI), Respiratory Tract Infection (RTI), Skin and Soft Tissue Infection (SSTI), and Gastrointestinal Tract Infection (GITI). These definitions often combine constitutional criteria (like fever or leukocytosis) with specific signs, symptoms, and sometimes laboratory findings, adding specificity to the infection. These specific, criteria-based definitions are crucial for consistent surveillance and outbreak identification in long-term care facilities.

The Main Costs of an Aged Care Outbreak

Infectious disease outbreaks in Australian and New Zealand aged care facilities are acknowledged as posing a significant economic challenge, impacting the costs of operation, staffing, and the overall sustainability of the aged care sector. While precise average cost figures for a single outbreak aren't readily available, the existing evidence points to a substantial financial burden driven by several key factors.

Drawing on estimates for a single infectious disease outbreak in Australian aged care, the total estimated cost can range significantly from $10,000 to over $100,000, depending on several factors. This estimate highlights the potential scale of expenditure, even without the availability of a definitive average number.

Specific examples of costs and impacts include:

Drawing on estimates for a single infectious disease outbreak in Australian aged care, the total estimated cost can range significantly from $10,000 to over $100,000, depending on several factors. This estimate highlights the potential scale of expenditure, even without the availability of a definitive average number.

Specific examples of costs and impacts include:

- COVID-19 expenditure in Australian aged care was reported at $6.69 per resident per day in 2022-2023

- Spending on agency staff to fill gaps during outbreaks in Australian aged care has been reported to have more than doubled in recent times.

- Western Australia residential care facilities experience an average of 95 gastroenteritis outbreaks each year, indicating the frequency of these costly events.

To provide a broader Australasian context, research on Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs) in New Zealand public hospitals estimated a significant economic burden annually. For 2021, the total estimated burden was $955 million. This was comprised of several major components:

- $792 million for the cost of Years of Life Lost (YoLL).

- $121 million for lost bed days.

- $43 million for Accident Compensation Commission (ACC) claims.

These New Zealand figures highlight the substantial economic consequences of HAIs, estimating 24,191 HAIs, 699 deaths, and 76,861 lost bed days in public hospitals in 2021. The burden measured by Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) for HAIs (24,165 DALYs) was shown to be greater than many other measured injuries and conditions in New Zealand, such as motor vehicle traffic crashes (20,328 DALYs) or colorectal cancer (24,012 DALYs). While these specific figures are for hospitals, they demonstrate the considerable economic impact of infections within the healthcare system, translating easily to significant costs in an aged care context.

The scale and duration of an outbreak are crucial factors to consider, as they directly influence the associated costs; longer or larger outbreaks will naturally incur greater expenses. Key cost drivers identified during an aged care outbreak include:

The scale and duration of an outbreak are crucial factors to consider, as they directly influence the associated costs; longer or larger outbreaks will naturally incur greater expenses. Key cost drivers identified during an aged care outbreak include:

- Staffing Expenditure: This is consistently highlighted as a significant cost of an outbreak due to increased demands on the workforce, reduced efficiency, staff fatigue, the necessity for replacement staff and overtime, and especially high costs associated with utilising agency staff. Staff shortages can also lead to a reduction in the number of available beds provided in a facility. (Estimated illustrative range: $5,000 - $50,000+ per outbreak).

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and Testing Costs: The need for a significant increase in available PPE results in substantial expenditure on procurement and safe disposal. Frequent testing adds to the overall costs, particularly with expensive PCR tests or procurement costs for rapid antigen tests (RATs). (Estimated range: PPE $1,000 - $10,000+, Testing $500 - $5,000+ per outbreak).

- Healthcare and Medical Expenses: These include the direct costs of treating infected residents, such as expenditure on antiviral medications, and the major cost driver of hospitalisation for residents requiring acute care. (Estimated range: $2,000 - $20,000+ per outbreak).

- Infection Prevention and Control Measures and Supplies (During the Outbreak): Implementing an increase in IPC measures during an outbreak adds costs for procuring cleaning and disinfection supplies, staff training on intensified protocols, and providing outbreak kits. (Estimated range: $500 - $5,000+ per outbreak).

- Facility Operational Costs: Outbreaks also increase regular operational expenses, including the requirement for more frequent and thorough cleaning and disinfection and proper management and disposal of clinical waste. (Estimated range: $1,000 - $10,000+ per outbreak).

The Social Impact of Disease Outbreaks

The social impact of disease outbreaks is far-reaching, affecting individuals, communities, and societies in profound ways. Psychological distress, anxiety, and depression will often surge during and after outbreaks, driven by the fear of infection, loss of loved ones, economic insecurity, and social isolation. These mental health challenges can have long-lasting consequences for individuals and communities, particularly among vulnerable groups and young adults.

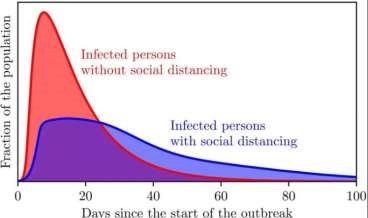

Fear of infection triggers significant behavioural changes, including adherence to social distancing measures, reduced travel, and shifts in consumerism. The extent of these behavioural changes and the overall "social response" to an outbreak are influenced by factors such as the perceived risk of the disease and the level of media involvement.

Outbreaks can increase existing social inequalities, leading to stigma, discrimination, and an erosion of social cohesion and trust. Vulnerable populations often experience a disproportionate burden of infection and its social and economic consequences. Trust in government and public health institutions can also decline during and after pandemics, potentially hindering future response efforts.

Fear of infection triggers significant behavioural changes, including adherence to social distancing measures, reduced travel, and shifts in consumerism. The extent of these behavioural changes and the overall "social response" to an outbreak are influenced by factors such as the perceived risk of the disease and the level of media involvement.

Outbreaks can increase existing social inequalities, leading to stigma, discrimination, and an erosion of social cohesion and trust. Vulnerable populations often experience a disproportionate burden of infection and its social and economic consequences. Trust in government and public health institutions can also decline during and after pandemics, potentially hindering future response efforts.

The Costs of Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) in Preventing Outbreaks

Given the significant costs incurred during an outbreak, investing in measures to prevent them becomes all-important. Robust infection prevention and control (IPC) practices are vitally important in aged care facilities, as many healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are preventable through appropriate measures. However, funding and implementing effective IPC also comes with costs, and these efforts often must compete for resources within facilities facing budget constraints.

While the financial burden of treating HAIs is understood, there is limited specific research showing the costs of efforts focused solely on preventing HAIs in long-term care settings. Despite this, it's clear that maintaining effective IPC requires ongoing expenditure. These ongoing costs include:

While the financial burden of treating HAIs is understood, there is limited specific research showing the costs of efforts focused solely on preventing HAIs in long-term care settings. Despite this, it's clear that maintaining effective IPC requires ongoing expenditure. These ongoing costs include:

- The procurement of cleaning and disinfection supplies.

- Costs associated with staff training on effective correct hygiene and infection control protocols.

Beyond routine IPC practices within facilities, the broader argument for proactive investment in prevention highlights the economic benefits. Investing in robust public health infrastructure, including strengthening surveillance systems and the public health workforce, is crucial for preparedness and prevention. This emphasises the economic benefits of proactive investment in preparedness to significantly outweigh the staggering costs associated with responding to full-scale pandemics. Implementing effective IPC programs, supported by strong evidence for reducing HAIs, is a key part of this beneficial proactive investment, and the significant burden of HAIs highlights the need for such national strategies.

Conclusion

While a precise average cost for a single infectious disease outbreak in an aged care facility in Australia or New Zealand remains elusive due to the variability of outbreaks and limited specific financial data, the available evidence points to a significant economic burden. COVID-19 and norovirus outbreaks appear to be particularly costly due to the intensive resources required for their management. The primary drivers of these costs include staffing expenditure, especially using replacement staff and overtime, as well as the procurement and utilisation of PPE and testing. Healthcare expenses, such as treatment and hospitalisation, also contribute substantially to the financial impact.

Government support is available to assist aged care facilities in Australia to manage these outbreaks through supplements and grants. However, challenges related to accessing and efficiently disbursing these funds have been reported by the sector. The scale and duration of an outbreak are critical factors influencing the overall cost, with prompt detection and response playing a vital role in mitigation. Regional variations in outbreak costs may exist, particularly for facilities in rural and remote areas. Further research is required to establish more precise financial benchmarks for different types of outbreaks and to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the total annual cost to the aged care sector.

PS: Learning from Outbreaks in History

Government support is available to assist aged care facilities in Australia to manage these outbreaks through supplements and grants. However, challenges related to accessing and efficiently disbursing these funds have been reported by the sector. The scale and duration of an outbreak are critical factors influencing the overall cost, with prompt detection and response playing a vital role in mitigation. Regional variations in outbreak costs may exist, particularly for facilities in rural and remote areas. Further research is required to establish more precise financial benchmarks for different types of outbreaks and to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the total annual cost to the aged care sector.

PS: Learning from Outbreaks in History

- Pandemic Estimated Mortality (Global)

- Estimated Economic Impact (USD)

- Key Social Consequences

Spanish Flu: 50-100 million, Significant GDP, Decline in social trust

Black Death: 75-200 million, Long-term economic restructuring, Decline of feudalism, social and cultural transformations

SARS: ~800 deaths, $30-80 billion, Fear, psychological trauma, impact on travel and tourism

Ebola (W. Africa): ~11,000 deaths, $30-50 billion, Community devastation, long-term sequelae, reversal of economic gains in affected countries

MERS: ~850 deaths, ~$8 billion (South Korea), Decline in tourism

Zika: Relatively low, ~$3.5 billion (Americas), Long-term healthcare costs for microcephaly

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

Follow us on Facebook and LinkedIn, comment and share.

Black Death: 75-200 million, Long-term economic restructuring, Decline of feudalism, social and cultural transformations

SARS: ~800 deaths, $30-80 billion, Fear, psychological trauma, impact on travel and tourism

Ebola (W. Africa): ~11,000 deaths, $30-50 billion, Community devastation, long-term sequelae, reversal of economic gains in affected countries

MERS: ~850 deaths, ~$8 billion (South Korea), Decline in tourism

Zika: Relatively low, ~$3.5 billion (Americas), Long-term healthcare costs for microcephaly

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

Follow us on Facebook and LinkedIn, comment and share.

Lyndon Forrest

Managing Director | CEO

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

Erica Callaghan

Marketing Manager

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Toni Sherriff

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Julie Hadfield

Accounts & Payroll

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Andrea Murray

Content Editor

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

Personally, I lived in the UK for 10 years. My two children were born in Scotland, and now both are living in Europe, one in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. I live close to Fairlie on the South Island of NZ, a beautiful part of the country, and I love being out of the city.

Princess

Customer Support

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Dianne Newey

Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

In my role, I promote Infection Prevention and Control, to RACF's and disability support services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

Caoimhe (Keva) Stewart

Clinical & Business Operations Manager

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Her move from nursing to customer service was driven by her passion for helping others, not just in clinical settings but also in ensuring that people have access to the resources and support they need. Now, Caoimhe applies her problem-solving skills, attention to detail, and communication expertise to her role, helping to create a positive and effective learning environment for all students.

Outside of work, Caoimhe enjoys travelling, staying active, and catching up with friends on the weekends. Whether in healthcare or customer service, she’s dedicated to making a meaningful difference and supporting people in their personal and professional growth.

Bridgette Mackie

Clinical Nurse Educator

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.