Oct 24

The Evolution of Long-Term Care

How it all began

For those of us working in residential care, we recognise that the modern aged care facility is a vital part of the healthcare system, providing essential, highly specialised support for managing frailty, multi-morbidity, and cognitive decline. However, to understand the current challenges—from staffing crises in Australia to funding debates in New Zealand—we need to first explore the global history of long-term care (LTC).

The institutions we manage today are not relics of ancient medicine, but results of poverty, philanthropy, and ultimately, post-war medical restructuring. The history of aged care is mainly a negotiation between the old cultural duty of filial piety and the modern need for professional institutional care. This blog explores this evolution, focusing on the different paths of Australia and New Zealand, and examines the growing global need to prioritise a dignified, culturally responsive care model.

The institutions we manage today are not relics of ancient medicine, but results of poverty, philanthropy, and ultimately, post-war medical restructuring. The history of aged care is mainly a negotiation between the old cultural duty of filial piety and the modern need for professional institutional care. This blog explores this evolution, focusing on the different paths of Australia and New Zealand, and examines the growing global need to prioritise a dignified, culturally responsive care model.

Poverty, Charity, and the Alms-house

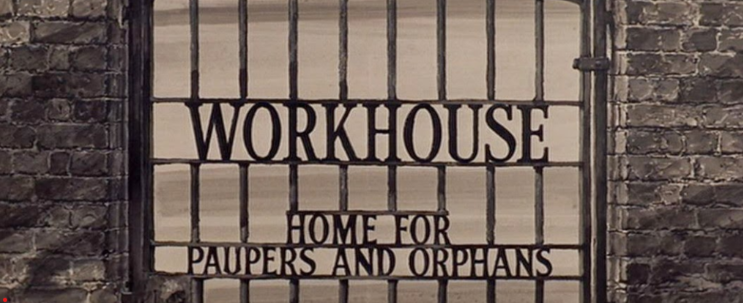

The origins of modern aged care trace back to almshouses or poorhouses, institutions that were never specifically created to care for the elderly. For centuries in Western societies, no distinction was made between someone who was simply poor and someone who was poor and old.

Residency in these ancestral facilities was granted for various reasons beyond just old age, including poverty and homelessness. The individuals accommodated were destitute, as well as others suffering from physical and mental disabilities (such as chronic illness or epilepsy), who were often refused entry by the early voluntary hospitals. Orphans and widows also lived in these crowded, multi-generational environments.

Although religious or charitable groups often ran the earliest facilities with the aim of offering hospitality, they frequently fell into decline. By the 18th and 19th centuries, especially in Europe and America, many had become stark, punitive institutions meant to discourage entry and to manage the poor at minimal public cost.

Residency in these ancestral facilities was granted for various reasons beyond just old age, including poverty and homelessness. The individuals accommodated were destitute, as well as others suffering from physical and mental disabilities (such as chronic illness or epilepsy), who were often refused entry by the early voluntary hospitals. Orphans and widows also lived in these crowded, multi-generational environments.

Although religious or charitable groups often ran the earliest facilities with the aim of offering hospitality, they frequently fell into decline. By the 18th and 19th centuries, especially in Europe and America, many had become stark, punitive institutions meant to discourage entry and to manage the poor at minimal public cost.

The Dawn of Specialisation and NZ Benevolence

The first major development occurred with philanthropic efforts aimed at separating the "worthy" elderly from the broader poor population. In the mid-19th century, private citizens, women’s associations, and church groups began establishing dedicated homes for the elderly "in reduced circumstances". These efforts, driven by a desire to provide charity and dignity, mark the true start of the idea of a dedicated ‘home for the aged’. The Te Hopai Trust in Wellington, New Zealand, founded in 1888, is a notable example, aiming to offer a respectable residence for older people without family support.

In New Zealand, before the introduction of old-age pensions in 1898, the elderly who were ill or unable to work depended on family support or charity. Due to the gender imbalance caused by colonisation, many elderly men found themselves without family by the early 20th century. Those unable to live independently often became residents of benevolent institutions. These places, established from the 1860s by provincial

charitable aid boards and religious institutions, were often described as grim and uncomfortable. While they maintained infirmaries, inmates suffering from dementia were historically sent to mental institutions.

Life in these institutions could be strictly regulated, especially for frail older people after the First World War. Inmates were required to surrender all belongings, abstain from alcohol, and bathe at least once a week. Despite these rules, elderly men often found ways of obtaining liquor, citing it as "one of the few comforts left to them."

Life in these institutions could be strictly regulated, especially for frail older people after the First World War. Inmates were required to surrender all belongings, abstain from alcohol, and bathe at least once a week. Despite these rules, elderly men often found ways of obtaining liquor, citing it as "one of the few comforts left to them."

From Charity to Clinical Care: The Post-War Pivot

Before 1900 in Australia, charitable aid from benevolent societies, sometimes with financial support from the government, was the main way people in need could get help. The economic depression of the 1890s and the growth of trade unions and the Labour parties during this time sparked a movement for welfare reform.

In 1900, New South Wales and Victoria passed laws introducing non-contributory pensions for those aged 65 and over. The old age pension and invalid pension were limited to people of "good character." By barring the use of government funding for residents of public almshouses, the legislation forced elderly and disabled individuals to seek care elsewhere. This financial restriction unintentionally "gave birth to the modern nursing home industry" by creating a demand and funding system for private long-term care.

The post-World War II period solidified the shift towards a medical model. Postwar legislation in the US encouraged hospitals to discharge patients once acute care was finished, and the war promoted a greater emphasis on rehabilitation. Consequently, private institutions adapted, welcoming a more diverse patient group that needed extended medical care. The nursing home moved decisively away from the charitable boarding house model to become an integral part of hospital services.

In 1900, New South Wales and Victoria passed laws introducing non-contributory pensions for those aged 65 and over. The old age pension and invalid pension were limited to people of "good character." By barring the use of government funding for residents of public almshouses, the legislation forced elderly and disabled individuals to seek care elsewhere. This financial restriction unintentionally "gave birth to the modern nursing home industry" by creating a demand and funding system for private long-term care.

The post-World War II period solidified the shift towards a medical model. Postwar legislation in the US encouraged hospitals to discharge patients once acute care was finished, and the war promoted a greater emphasis on rehabilitation. Consequently, private institutions adapted, welcoming a more diverse patient group that needed extended medical care. The nursing home moved decisively away from the charitable boarding house model to become an integral part of hospital services.

Australasia’s Dual Trajectory: Institutionalisation and Crisis

The post-war shift accelerated in New Zealand, where more church-run and private rest homes appeared, especially as women began to outnumber men in older age groups. By the mid-1970s, New Zealand had one of the highest rates of rest-home residency in the Western world.

New Zealand: A Regulated, Subsidised System

New Zealand: A Regulated, Subsidised System

Today, while 'rest home' is a broad term, care services include rest-home care, long-term hospital care, dementia care, and psychogeriatric care. Residential facilities may provide some or all of these services.

The system relies heavily on government subsidies. Commercial and non-governmental facilities receive substantial payments from district health boards (DHBs) for caring for older people who cannot afford their own care. This means that care providers are effectively subsidised by the government, regardless of whether they are for-profit or not.

Access to subsidised residential care is strictly regulated. It always involves needs assessments conducted by local Needs Assessment and Service Coordination (NASC) agencies. Assessors evaluate mobility, health issues, family support networks, and the individual’s capacity to manage personal hygiene and household tasks. Long-term residential care is recommended only if needs are assessed as ‘high’ or ‘very high’; otherwise, support to stay at home is provided. An assessment of income and assets follows this to determine eligibility for the Residential Care Subsidy. For those with partners, the family home, a car, and pre-paid funeral expenses are excluded from the assets assessment.

Despite the growth of the rest home industry, with many facilities owned by overseas companies seeking profits, the 2013 census showed that 92% of people aged 65 or over lived in private homes. Only 5% lived in residential care facilities, and of those, more than half were over 85. Those entering residential care are increasingly older and have higher levels of disability, which creates a greater need for specialist care.

The sector’s workforce is predominantly composed of women. While rest homes employ professionally qualified staff, including registered nurses and occupational therapists, most caregivers do not have professional nursing qualifications. A landmark moment occurred in 2012 when caregiver Kristine Bartlett filed an equal pay claim, arguing that the low pay rate was due to the work being mostly done by women, which breached the Equal Pay Act 1972. After years of legal battles that went to the Supreme Court, a settlement was reached in April 2017, resulting in mandated increases in hourly wages for aged care workers funded through Vote Health.

The system relies heavily on government subsidies. Commercial and non-governmental facilities receive substantial payments from district health boards (DHBs) for caring for older people who cannot afford their own care. This means that care providers are effectively subsidised by the government, regardless of whether they are for-profit or not.

Access to subsidised residential care is strictly regulated. It always involves needs assessments conducted by local Needs Assessment and Service Coordination (NASC) agencies. Assessors evaluate mobility, health issues, family support networks, and the individual’s capacity to manage personal hygiene and household tasks. Long-term residential care is recommended only if needs are assessed as ‘high’ or ‘very high’; otherwise, support to stay at home is provided. An assessment of income and assets follows this to determine eligibility for the Residential Care Subsidy. For those with partners, the family home, a car, and pre-paid funeral expenses are excluded from the assets assessment.

Despite the growth of the rest home industry, with many facilities owned by overseas companies seeking profits, the 2013 census showed that 92% of people aged 65 or over lived in private homes. Only 5% lived in residential care facilities, and of those, more than half were over 85. Those entering residential care are increasingly older and have higher levels of disability, which creates a greater need for specialist care.

The sector’s workforce is predominantly composed of women. While rest homes employ professionally qualified staff, including registered nurses and occupational therapists, most caregivers do not have professional nursing qualifications. A landmark moment occurred in 2012 when caregiver Kristine Bartlett filed an equal pay claim, arguing that the low pay rate was due to the work being mostly done by women, which breached the Equal Pay Act 1972. After years of legal battles that went to the Supreme Court, a settlement was reached in April 2017, resulting in mandated increases in hourly wages for aged care workers funded through Vote Health.

Australia: Privatisation and Quality Failure

At the time of Federation in 1901, elders in Australia were mostly cared for by daughters, aunts, and women in their extended families. Over the past century, pensions and aged care became the responsibility of the federal government. By the late 1980s, demographic projections warned that the post-WWII baby boom would lead to a large ageing population, with 1 in 5 Australians expected to be over 65 by 2030.

Historically, aged care facilities included community-run or non-profit religious hostels for low-care residents and "Nursing Homes" for more frail, high-care residents suffering from mobility issues, multiple health conditions, and cognitive decline, including dementia.

A significant change took place following a review of funding and staffing costs around 1996. The Howard Federal Government decided to promote private for-profit companies to invest in new aged care facilities. The 1997 Aged Care Act enabled providers to develop modern buildings where most residents would pay a bond along with private fees, while only a small portion (up to 20%) of places remained fully funded by the government. Importantly, this legislation also imposed a cap on the total government expenditure for aged care, set during annual budget reviews.

A direct result of this shift was the phenomenon of "cutting the nursing out of nursing homes." Nurse wages did not keep up with those in the acute public and private hospital sectors after 1997, leading to the gradual replacement of registered nurses with personal care attendants (PCAs) as nurses retired or returned to the public sector.

As resident frailty and dependency increased, the number of skilled, qualified staff decreased. Residents became older and sicker, with declining mobility; the number of cognitively impaired people in residential care is estimated at 50–70% of residents. This reduction in nursing expertise severely limited the capacity to manage the medical, emotional, cognitive, and pharmacological needs of people nearing the end of life.

Systemic issues worsened due to regulatory failures. Oversight diminished, and management was usually informed before inspections, making it hard to assess the true level of care. Despite numerous media reports of neglect and major abuse cases, efforts to tighten regulation continued to fall short. Today, many large private facilities (often 80–120 beds) are staffed by only one registered nurse, a few enrolled nurses, and mostly unregulated, unregistered carers.

This systemic failure prompted the Aged Care Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. After 18 inquiries, the interim report was aptly titled "Neglect," confirming widespread dysfunction and declining standards. The final report recommended 148 major reforms, aiming for a complete overhaul of governance, accountability, and funding. Experts emphasise that denying older Australians their human right to a peaceful, dignified, and fulfilling end of life is inexcusable and unethical. The industry has now advocated for a new, comprehensive Human Rights-based Aged Care Act to ensure transparency and accountability.

Historically, aged care facilities included community-run or non-profit religious hostels for low-care residents and "Nursing Homes" for more frail, high-care residents suffering from mobility issues, multiple health conditions, and cognitive decline, including dementia.

A significant change took place following a review of funding and staffing costs around 1996. The Howard Federal Government decided to promote private for-profit companies to invest in new aged care facilities. The 1997 Aged Care Act enabled providers to develop modern buildings where most residents would pay a bond along with private fees, while only a small portion (up to 20%) of places remained fully funded by the government. Importantly, this legislation also imposed a cap on the total government expenditure for aged care, set during annual budget reviews.

A direct result of this shift was the phenomenon of "cutting the nursing out of nursing homes." Nurse wages did not keep up with those in the acute public and private hospital sectors after 1997, leading to the gradual replacement of registered nurses with personal care attendants (PCAs) as nurses retired or returned to the public sector.

As resident frailty and dependency increased, the number of skilled, qualified staff decreased. Residents became older and sicker, with declining mobility; the number of cognitively impaired people in residential care is estimated at 50–70% of residents. This reduction in nursing expertise severely limited the capacity to manage the medical, emotional, cognitive, and pharmacological needs of people nearing the end of life.

Systemic issues worsened due to regulatory failures. Oversight diminished, and management was usually informed before inspections, making it hard to assess the true level of care. Despite numerous media reports of neglect and major abuse cases, efforts to tighten regulation continued to fall short. Today, many large private facilities (often 80–120 beds) are staffed by only one registered nurse, a few enrolled nurses, and mostly unregulated, unregistered carers.

This systemic failure prompted the Aged Care Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. After 18 inquiries, the interim report was aptly titled "Neglect," confirming widespread dysfunction and declining standards. The final report recommended 148 major reforms, aiming for a complete overhaul of governance, accountability, and funding. Experts emphasise that denying older Australians their human right to a peaceful, dignified, and fulfilling end of life is inexcusable and unethical. The industry has now advocated for a new, comprehensive Human Rights-based Aged Care Act to ensure transparency and accountability.

The Global Imperative: Alternative Care and Cultural Lenses

While institutional care remains essential for those with complex, high needs, the global trend—especially in countries with the oldest populations—is moving decisively away from institutionalisation. The preferred option worldwide is increasingly to provide high-quality, government-funded Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS).

Ageing in Place: The Australasian Preference

This philosophy is strongly reflected in New Zealand policy, with 'Ageing in Place' and the 'Positive Ageing Strategy' introduced in 2001. Older people overwhelmingly prefer to remain in their own homes and maintain community connections. Support services include the provision of Meals on Wheels, mobility aids, and household help by district health boards. As a result, the proportion of people over 85 who live at home rather than in residential care has increased.

Specialised housing options, such as retirement villages with optional support services, help many stay independent longer. This is especially useful for couples where one

Specialised housing options, such as retirement villages with optional support services, help many stay independent longer. This is especially useful for couples where one

partner needs more support than the other, allowing them to continue living together. Indeed, the 2013 census showed that 92% of people aged 65 or over lived in private homes.

The Cultural Divide: Filial Piety vs. Autonomy

The preference for 'Ageing in Place' is strongly connected to long-standing cultural differences in elder care.

In individualistic Western societies, including Australia and New Zealand, the cultural emphasis is heavily on autonomy. Generally, there is no societal expectation for multi-generational cohabitation; children are expected to leave home, and parents are expected to maintain independent living. When needs arise, this dynamic results in what is called "intimacy at a distance": adult children provide vital financial, emotional, and logistical support but rarely offer 24/7 hands-on care within the same household.

This sharply contrasts with collectivist societies in Africa, Asia, and parts of Southern and Eastern Europe, where filial piety often requires children to provide direct, hands-on care as a fundamental moral duty.

The Outsourced Care Gap

In individualistic Western societies, including Australia and New Zealand, the cultural emphasis is heavily on autonomy. Generally, there is no societal expectation for multi-generational cohabitation; children are expected to leave home, and parents are expected to maintain independent living. When needs arise, this dynamic results in what is called "intimacy at a distance": adult children provide vital financial, emotional, and logistical support but rarely offer 24/7 hands-on care within the same household.

This sharply contrasts with collectivist societies in Africa, Asia, and parts of Southern and Eastern Europe, where filial piety often requires children to provide direct, hands-on care as a fundamental moral duty.

The Outsourced Care Gap

The dependence on formal systems in the West has led to a significant challenge: the Care Gap. People are living longer, often with complex, long-term conditions such as multi-morbidity and dementia. This specialised, physical care frequently requires professional expertise that an employed adult child may not be able to provide.

Additionally, economic shifts—such as the increased participation of women in the workforce (who historically bore most of the informal care) and soaring housing costs—have diminished the availability of family carers.

The modern paradigm is defined not by "family abandonment," but by the outsourcing of clinical complexity. While the family remains the emotional anchor and primary coordinator, the provision of intensive clinical support relies on professional systems. Although HCBS is preferred, most of the funding in many Western countries still goes to institutions because of the high cost of highly complex, 24-hour care that families cannot manage.

Additionally, economic shifts—such as the increased participation of women in the workforce (who historically bore most of the informal care) and soaring housing costs—have diminished the availability of family carers.

The modern paradigm is defined not by "family abandonment," but by the outsourcing of clinical complexity. While the family remains the emotional anchor and primary coordinator, the provision of intensive clinical support relies on professional systems. Although HCBS is preferred, most of the funding in many Western countries still goes to institutions because of the high cost of highly complex, 24-hour care that families cannot manage.

Conclusion

The evolution of aged care—from the punitive 18th-century poorhouse to the specialised residential facilities of the 21st century—reflects a profound moral and medical shift. The decline of the charitable poorhouse system, key legislative milestones, and the post-war emphasis on clinical efficiency have shaped this path.

In New Zealand, this resulted in high rates of early institutionalisation and notable victories for pay equity. In Australia, it caused a crisis in quality and staffing after privatisation, as thoroughly documented by the damning findings of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety.

The key lesson for healthcare workers and policymakers is clear: while formal systems are essential for managing high clinical needs, the fundamental human needs for comfort, dignity, and family connection must always be prioritised. The future of aged care, across Australasia and worldwide, calls for the integration of specialised professional care with strong community and family support networks. We must insist on systems that fundamentally respect the human rights of our elders.

In New Zealand, this resulted in high rates of early institutionalisation and notable victories for pay equity. In Australia, it caused a crisis in quality and staffing after privatisation, as thoroughly documented by the damning findings of the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety.

The key lesson for healthcare workers and policymakers is clear: while formal systems are essential for managing high clinical needs, the fundamental human needs for comfort, dignity, and family connection must always be prioritised. The future of aged care, across Australasia and worldwide, calls for the integration of specialised professional care with strong community and family support networks. We must insist on systems that fundamentally respect the human rights of our elders.

Read more of our blogs on the HUB and the IPS website. If you would like to learn more about a particular subject, let us know.

Lyndon Forrest

Managing Director | CEO

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

Erica Callaghan

Marketing Manager

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Toni Sherriff

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Julie Hadfield

Accounts & Payroll

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Andrea Murray

Content Editor

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

Personally, I lived in the UK for 10 years. My two children were born in Scotland, and now both are living in Europe, one in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. I live close to Fairlie on the South Island of NZ, a beautiful part of the country, and I love being out of the city.

Princess

Customer Support

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Dianne Newey

Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

In my role, I promote Infection Prevention and Control, to RACF's and disability support services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

Caoimhe (Keva) Stewart

Clinical & Business Operations Manager

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Her move from nursing to customer service was driven by her passion for helping others, not just in clinical settings but also in ensuring that people have access to the resources and support they need. Now, Caoimhe applies her problem-solving skills, attention to detail, and communication expertise to her role, helping to create a positive and effective learning environment for all students.

Outside of work, Caoimhe enjoys travelling, staying active, and catching up with friends on the weekends. Whether in healthcare or customer service, she’s dedicated to making a meaningful difference and supporting people in their personal and professional growth.

Bridgette Mackie

Clinical Nurse Educator

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.