Jul 15

The Know–Do Gap

Why Best Practices Still Miss the Mark

Older people living in residential aged care facilities (RACFs) are particularly vulnerable to infections such as influenza, COVID-19, and norovirus. This vulnerability stems from high rates of frailty and comorbidity, combined with close contact with staff, other residents, and visitors in communal areas. Given these risks, high-quality infection prevention and control (IPC) practices are vital in this setting.

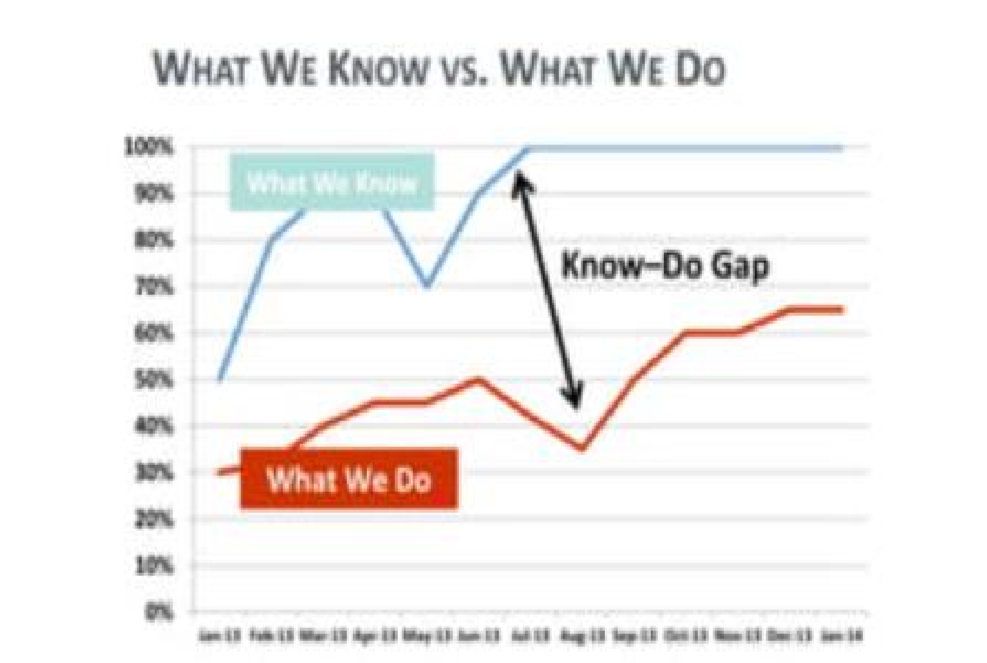

However, despite extensive knowledge and training, a persistent challenge remains: the "Know-Do" gap. This fundamental divide describes the disparity between what is understood from scientific research and evidence-based guidelines ("know") and what is consistently applied in actual clinical care settings ("do"). It highlights the difficulties in translating robust scientific findings and established best practices into routine, standardised care. In Australia, one study found infection rates in RACFs to range from 2.7% to 3.1%, with similar statistics reported in New Zealand. It is therefore crucial to understand and address this gap to protect our most vulnerable citizens.

However, despite extensive knowledge and training, a persistent challenge remains: the "Know-Do" gap. This fundamental divide describes the disparity between what is understood from scientific research and evidence-based guidelines ("know") and what is consistently applied in actual clinical care settings ("do"). It highlights the difficulties in translating robust scientific findings and established best practices into routine, standardised care. In Australia, one study found infection rates in RACFs to range from 2.7% to 3.1%, with similar statistics reported in New Zealand. It is therefore crucial to understand and address this gap to protect our most vulnerable citizens.

Unpacking the "Know-Do" Gap: More Than Just a Lack of Knowledge

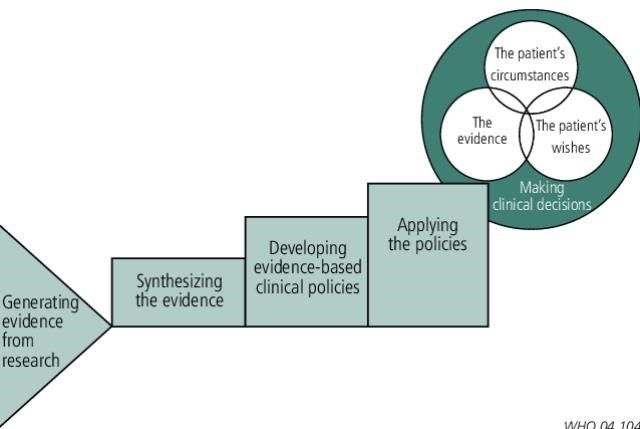

The "know" component of this gap is far from inflexible. Simply disseminating information broadly is usually insufficient, as the understanding of "knowledge" varies significantly depending on the audience and context. A medical researcher's information needs, for instance, differ vastly from those of a frontline care worker or a

policymaker. This means that for knowledge to be truly effective, it must be accessible, relevant, and interpretable by diverse groups, enabling them to apply it within their specific practice contexts.

The persistence of this "Know-Do" gap is not merely an academic curiosity; it can have profound consequences for the well-being of older adults. The failure to translate effective interventions into practice is a significant barrier to achieving health equity worldwide. This lag between knowing and doing can result in millions of patients receiving inaccurate or delayed diagnoses and suboptimal care each year. Astonishingly, it can take an average of 17 years for research-based practices to integrate into clinical settings, with many interventions never reaching their full potential. This substantial delay prevents scientific advancements from reaching those who could benefit most, particularly in resource-constrained environments like aged care. Conversely, closing evidence-practice gaps by reducing inappropriate care leads to better patient outcomes, greater efficiency, and less wastage of resources.

The persistence of this "Know-Do" gap is not merely an academic curiosity; it can have profound consequences for the well-being of older adults. The failure to translate effective interventions into practice is a significant barrier to achieving health equity worldwide. This lag between knowing and doing can result in millions of patients receiving inaccurate or delayed diagnoses and suboptimal care each year. Astonishingly, it can take an average of 17 years for research-based practices to integrate into clinical settings, with many interventions never reaching their full potential. This substantial delay prevents scientific advancements from reaching those who could benefit most, particularly in resource-constrained environments like aged care. Conversely, closing evidence-practice gaps by reducing inappropriate care leads to better patient outcomes, greater efficiency, and less wastage of resources.

Fundamental Challenges for IPC Practices Among Healthcare Workers (Despite Education)

One of the most notable findings from a study assessing IPC practices in Australian RACFs using scenarios revealed 11 evidence-practice gaps. These gaps weren't just about complex procedures; they also included fundamental actions essential for infection control. For example, the study identified gaps in performing hand hygiene before touching a resident, such as when assisting with a transfer. Another key gap was not wearing protective eyewear or a face shield before taking a nasal or throat swab from a resident suspected of having a respiratory viral infection. Even a seemingly basic sequence, like disposing of wipes, doffing and disposing of gloves, and then performing hand hygiene after disinfecting a contaminated surface, was identified as an area where practices fell short. These findings highlight that the challenge goes beyond simply knowing what to do.

This highlights a common gap between knowing and doing. Healthcare workers may clearly understand correct procedures in scenarios but often fail to apply them consistently during actual clinical interactions. This reveals a pattern of "consistently inconsistent" healthcare delivery. Factors beyond mere understanding, such as ingrained habits, time constraints, or the perceived demands of real situations, can lead to non-compliance, sometimes even overriding best-known practices. For example, studies have shown that healthcare professionals administer potentially harmful treatments to actual patients at a much higher rate (71.9%) than they indicated in brief case descriptions (20.9%), despite possessing the correct knowledge. This also indicates that interventions need to go beyond basic education, including practical training, simulation, and strategies to address behavioural and contextual factors that influence real-time decision-making and performance.

Furthermore, gaps in caregiver practice are clear in their understanding and response to residents' needs. HCWs often underestimate or fail to completely understand older adults' needs, particularly concerning “Instrumental Activities of Daily Living” (IADLs) and emotional well-being. Research indicates that less than half of HCWs accurately understood residents' needs for household chores (30%), money management (43%), or the vital importance for older adults to feel they are "playing a role" (41%). A notable "disconnect" also exists between how residents see their own care needs and how caregivers observe these needs. Residents, particularly those with depressive symptoms, may underreport or minimise practical concerns such as mobility limitations. Moreover, even when unmet needs exist, they result in inadequate care provision.

These issues are widespread. Studies on nurses in geriatric care show a significant "knowledge and practice gap." One study found that while 57.2% of participants had good knowledge, only 45.3% showed good practice, highlighting a notable discrepancy. Another study reported that most nurses (69%) had poor knowledge, an unfavourable attitude, and inadequate practice regarding care for elderly patients. These problems may result from limited education, a disconnect between theory and practice, and outdated protocols.

This highlights a common gap between knowing and doing. Healthcare workers may clearly understand correct procedures in scenarios but often fail to apply them consistently during actual clinical interactions. This reveals a pattern of "consistently inconsistent" healthcare delivery. Factors beyond mere understanding, such as ingrained habits, time constraints, or the perceived demands of real situations, can lead to non-compliance, sometimes even overriding best-known practices. For example, studies have shown that healthcare professionals administer potentially harmful treatments to actual patients at a much higher rate (71.9%) than they indicated in brief case descriptions (20.9%), despite possessing the correct knowledge. This also indicates that interventions need to go beyond basic education, including practical training, simulation, and strategies to address behavioural and contextual factors that influence real-time decision-making and performance.

Furthermore, gaps in caregiver practice are clear in their understanding and response to residents' needs. HCWs often underestimate or fail to completely understand older adults' needs, particularly concerning “Instrumental Activities of Daily Living” (IADLs) and emotional well-being. Research indicates that less than half of HCWs accurately understood residents' needs for household chores (30%), money management (43%), or the vital importance for older adults to feel they are "playing a role" (41%). A notable "disconnect" also exists between how residents see their own care needs and how caregivers observe these needs. Residents, particularly those with depressive symptoms, may underreport or minimise practical concerns such as mobility limitations. Moreover, even when unmet needs exist, they result in inadequate care provision.

These issues are widespread. Studies on nurses in geriatric care show a significant "knowledge and practice gap." One study found that while 57.2% of participants had good knowledge, only 45.3% showed good practice, highlighting a notable discrepancy. Another study reported that most nurses (69%) had poor knowledge, an unfavourable attitude, and inadequate practice regarding care for elderly patients. These problems may result from limited education, a disconnect between theory and practice, and outdated protocols.

Key Reasons for Non-Adherence to IPC Practices

The persistence of the "Know-Do" gap is complex, arising from an interaction of individual, systemic, and cultural factors.

1. Individual & Behavioural Factors

- Attribution of Responsibility: HCWs often concentrate on their perceived duties while simultaneously assigning specific IPC tasks to others based on traditional professional roles. For instance, a consultant physician might say, "I work as a physician, so I don't do things; I do a lot of thinking, talking, and organising." This can lead to confusion and disagreements, as the doctor is blamed by the nurse for an action, and vice versa, even for routine tasks such as managing catheters. Although collective responsibility is acknowledged, there is a lack of clarity about who is responsible for addressing suboptimal practices, which creates tensions. Nurses and pharmacists may feel responsible but lack the authority to enforce practices beyond their official duties.

- Prioritisation and Risk Appraisal: HCWs acknowledge IPC requirements but may not assign high priority due to other competing demands and limited resources. Personal experience is highly valued and can override policy, leading to "shortcuts" when balancing healthcare-associated infection (HAI) risks with other patient needs. A junior doctor might justify not removing a peripheral line at three days because of "clinical need of having a line in people who were difficult to get a line," even if policy states otherwise. Resource constraints directly contribute to "cutting corners," with a senior nurse saying, "when they don't do it, it's because we're too busy, short-staffed, too stretched; they're cutting that corner when they feel under pressure to prioritise other things."

- Hierarchy of Influence: Traditional hierarchical barriers often stop staff from challenging non-compliant colleagues, particularly senior doctors. A consultant physician noted, "there's still an element of apprehension, challenging a surgeon who comes wearing a coat and goes in and touches a patient." Junior staff may struggle to break from the norms set by seniors. Conversely, senior doctors might prefer more independence, ignoring protocols, which creates barriers to interdisciplinary communication.

2. Systemic & Organisational Barriers

Beyond individual behaviours, the infrastructure and operational realities of aged care present substantial challenges:

- Inadequate Infrastructure and Resources: This includes shortages of consumables, poorly designed facilities, and insufficient equipment. Caregivers often face resource shortages and tight schedules, which limit their ability to stay current with new developments or dedicate sufficient time to patient care.

- Fragmented Systems: Existing healthcare models often lack integration, leading to disorganised services, suboptimal outcomes, and poor communication between providers. This can result in unnecessary tests, procedures, and hospitalisations.

- Staffing Shortages: Insufficient staffing is a major problem in hospitals and aged care, causing increased workload, fewer training opportunities, and an inability to dedicate enough time to patient care. It can also lead to untrained staff taking on duties they are unable to perform safely.

- Lack of Organisational Commitment: An unsupportive environment, caused by management's insufficient support for evidence-based practice (EBP) implementation, makes it harder to adopt new procedures.

3. Cultural Factors

Deeply embedded cultural norms can strongly hinder change.

- Resistance to Change: Deeply ingrained cultural norms like "the power of precedent" ("We've always done it that way") act as formidable barriers, preventing the adoption of new knowledge into practice.

- Individual preferences can override best practices: Healthcare professionals may focus on personal choices, causing inconsistencies in care delivery.

- Rigid Cultures: "Rules-orientated nursing cultures" and hierarchical structures can impede innovation. Negative attitudes towards EBP among nurses are statistically associated with limited knowledge and practice. An emphasis on "rugged individualism" rather than standardisation can also block progress.

4. Patient and Caregiver-Related Challenges

Factors directly related to older adults and their informal caregivers also contribute to the gap:

- Low Health Literacy and Cognitive Impairment: Older adults' difficulty in absorbing and retaining important health information, caused by cognitive issues or low health literacy, is a significant obstacle. Many struggle to understand and use medical documents, forms, or charts.

- Socioeconomic Disparities: Financial barriers, such as having to forgo essential medications to cover necessities like food or rent, are common among older adults from lower-income backgrounds. A lack of transportation can also limit access to necessary care and follow-up. Social isolation and loneliness are also important issues.

- Resident Non-Adherence: Residents might not follow recommendations due to misunderstandings, incorrect completion, forgetfulness, or outright disregard of advice. This is affected by a complex range of factors, including personal beliefs, attitudes, social norms, and emotional health issues such as depression. Residents may also feel overwhelmed or perceive a lack of support, which can

lead

them to miss critical tests or skip follow-up appointments. These issues show how systemic shortcomings can worsen resident vulnerabilities.

5. Towards a Solution: Bridging the "Know-Do" Gap

Addressing this deep "Know-Do" gap requires a comprehensive and integrated approach that works on individual, organisational, and systemic levels. It's not enough to identify the issue; we must actively support the implementation and ongoing use of best practices.

- Leveraging Implementation Science: This is a dedicated and evolving field focused on integrating research findings into routine practice. It provides structured frameworks, such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework, and the Knowledge-to-Action (KTA) framework, to guide these efforts. Notably, a specific "Implementation Framework for Aged Care (IFAC)" has been co-designed with stakeholders to be fit-for-purpose in community and residential aged care. This discipline focuses on the "how-to" of intervention application, moving beyond merely knowing to doing.

- Enhancing Continuous Education and Training: Ongoing and comprehensive education and training programs are vital for equipping HCWs and care teams with the necessary knowledge, skills, and confidence. This includes developing skills in understanding EBP principles, locating and assessing evidence, and applying it directly to practice. Training programs have proven to have tangible benefits, including improved patient outcomes, enhanced care team capabilities, better compliance, and increased confidence and retention. Importantly, managerial support, particularly through relational leadership styles, plays a crucial role in embedding new knowledge and skills into everyday practice.

- Fostering Stakeholder Engagement and Collaboration: Actively involving patients, families, healthcare providers, and policymakers from the outset is essential. Their participation offers valuable insights that shape planning and facilitate smoother implementation, as those involved early are more likely to support and champion the intervention. Collaboration with interdisciplinary teams is vital, allowing professionals to share diverse expertise and perspectives. Family involvement plays a key role in enhancing the quality, safety, and emotional well-being of residents, ensuring preferences are prioritised and fostering a collaborative environment. The consistent advocacy for early and ongoing engagement contrasts sharply with simply "pushing information out".

- Adopting Technology and Digital Solutions: Using technology presents significant opportunities to identify care gaps, streamline processes, enhance communication, and personalise care. Artificial intelligence (AI) can detect care gaps and predict the best engagement methods for personalised interventions. Electronic Health Records (EHRs) facilitate the sharing of research findings and improve documentation. At the same time, Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSSs) support nursing practice, leading to greater accuracy and enhanced patient safety. Mobile technologies and telehealth platforms can increase access to evidence and care when needed. However, successful implementation faces several barriers, including caregivers' perceptions that older adults are disinterested in technology, a preference for familiar approaches, and concerns about the cost and digital skills required. Therefore, a human-centred design approach, combined with comprehensive training and ongoing support, is essential.

- Developing an Evidence-Based Culture: A fundamental change in organisational culture is needed, shifting from tradition to a shared commitment to inquiry, safety, and ongoing improvement. This requires creating enlightened work environments that empower staff by removing fear and distrust. Building an EBP culture involves actively promoting curiosity, offering resources and support, and recognising and rewarding those who adopt evidence-based approaches. Key challenges include overcoming resistance to change and addressing non-supportive atmospheres.

- Addressing Social Determinants of Health (SDOH): Recognising and actively tackling social, economic, and environmental factors is essential, as they often create significant barriers for older adults to access and follow through with recommended care, thus broadening the "Know-Do" gap. This includes financial insecurity (e.g., inability to afford medications), lack of transportation, and social isolation. Interventions should be patient-centred, culturally sensitive, and directly address SDOH to remove external obstacles preventing individuals from "doing" what they "know" is beneficial.

Conclusion: A Continuous Journey for Quality Aged Care

The persistent "Know-Do" gap in residential aged care, which is highly relevant for Australia and New Zealand, presents a complex challenge that directly affects the quality, safety, and fairness of services for older adults. It is a systemic decline, resulting in delayed diagnoses, medication errors, more hospitalisations, and preventable deaths. This burden also falls more heavily on caregivers, resulting in increased stress, financial pressure, burnout, and high staff turnover rates.

Closing this gap is not a single task but a continuous journey. It requires a systemic commitment to fostering learning, collaboration, and adaptability. By strategically applying implementation science, enhancing ongoing education, genuinely engaging all stakeholders, thoughtfully adopting technology, cultivating an evidence-based culture, and addressing the social determinants of health, we can ensure that the wealth of knowledge we hold is consistently translated into real improvements in the lives of older adults and those who care for them. This commitment is vital for upholding the ethical obligation of delivering high-quality, safe, and person-centred aged care for all.

Follow this blog and others in the series dedicated to the “Know-Do” of caring for the aged. Available on our website.

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

Follow us on Facebook and LinkedIn – share and comment, we appreciate all feedback.

Any questions? Contact EVE or our friendly team at support@infectioncontrol.care

Closing this gap is not a single task but a continuous journey. It requires a systemic commitment to fostering learning, collaboration, and adaptability. By strategically applying implementation science, enhancing ongoing education, genuinely engaging all stakeholders, thoughtfully adopting technology, cultivating an evidence-based culture, and addressing the social determinants of health, we can ensure that the wealth of knowledge we hold is consistently translated into real improvements in the lives of older adults and those who care for them. This commitment is vital for upholding the ethical obligation of delivering high-quality, safe, and person-centred aged care for all.

Follow this blog and others in the series dedicated to the “Know-Do” of caring for the aged. Available on our website.

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

Follow us on Facebook and LinkedIn – share and comment, we appreciate all feedback.

Any questions? Contact EVE or our friendly team at support@infectioncontrol.care

Lyndon Forrest

Managing Director | CEO

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

Erica Callaghan

Marketing Manager

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Toni Sherriff

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Julie Hadfield

Accounts & Payroll

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Andrea Murray

Content Editor

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

Personally, I lived in the UK for 10 years. My two children were born in Scotland, and now both are living in Europe, one in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. I live close to Fairlie on the South Island of NZ, a beautiful part of the country, and I love being out of the city.

Princess

Customer Support

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Dianne Newey

Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

In my role, I promote Infection Prevention and Control, to RACF's and disability support services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

Caoimhe (Keva) Stewart

Clinical & Business Operations Manager

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Her move from nursing to customer service was driven by her passion for helping others, not just in clinical settings but also in ensuring that people have access to the resources and support they need. Now, Caoimhe applies her problem-solving skills, attention to detail, and communication expertise to her role, helping to create a positive and effective learning environment for all students.

Outside of work, Caoimhe enjoys travelling, staying active, and catching up with friends on the weekends. Whether in healthcare or customer service, she’s dedicated to making a meaningful difference and supporting people in their personal and professional growth.

Bridgette Mackie

Clinical Nurse Educator

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.