Oct 30

The Neurodegenerative Frontier

Dementia, Alzheimer’s and Care

For clinicians, researchers, and allied health professionals, the complex range of cognitive decline presents one of the greatest challenges in modern medicine. Confusion often results from the interchangeable use of terms like dementia, Alzheimer's disease (AD), and normal aging, leading to fragmented care pathways and missed opportunities for early intervention. Recent breakthroughs in disease-modifying therapies and evolving models of person-centred care require a precise understanding of the foundational science and the integrated support structures available.

This comprehensive overview aims to sharpen clinical distinctions, clarify the specific underlying neuropathology of AD, review the latest pharmacological and research advances, and highlight the vital role of strong rehabilitation and specialised care models in improving patient outcomes.

This comprehensive overview aims to sharpen clinical distinctions, clarify the specific underlying neuropathology of AD, review the latest pharmacological and research advances, and highlight the vital role of strong rehabilitation and specialised care models in improving patient outcomes.

Cognitive Changes in the Aging Process

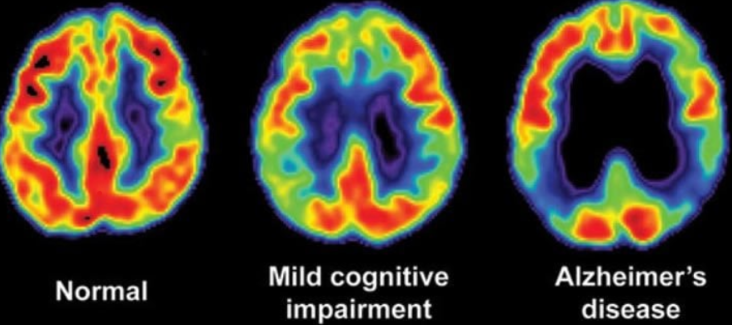

The transition from normal cognitive aging to disabling cognitive impairment depends on careful diagnostic differentiation. The key difference lies mainly in the severity of the impairment and its impact on a person's capacity to live independently.

1. Dementia: The Clinical Syndrome

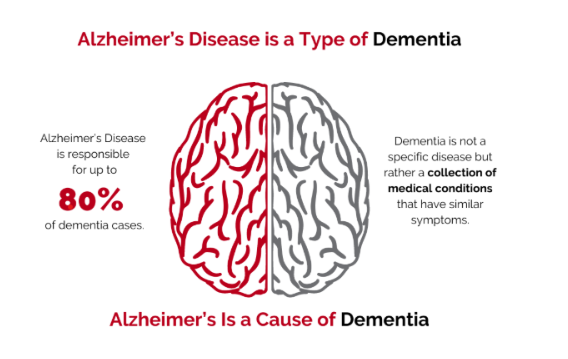

Dementia is not a specific diagnosis or disease, but an umbrella term used to describe a group of debilitating symptoms.

Dementia is diagnosed when cognitive symptoms—such as memory loss, language difficulties, or problems with thinking and problem-solving—become severe enough to disrupt daily life. This disruption to daily living and independence is the threshold that defines the condition. It is progressive, usually worsening over time, and results from damage to brain cells caused by various diseases or injuries.

Dementia is diagnosed when cognitive symptoms—such as memory loss, language difficulties, or problems with thinking and problem-solving—become severe enough to disrupt daily life. This disruption to daily living and independence is the threshold that defines the condition. It is progressive, usually worsening over time, and results from damage to brain cells caused by various diseases or injuries.

2. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD): The Specific Pathology

Alzheimer's disease differs fundamentally from dementia because it is a specific, progressive neurodegenerative condition. It is the leading cause of dementia, responsible for an estimated 60–70% of cases. Similar to the syndrome it produces, AD progression can be severe enough to disrupt daily life and tends to worsen over time.

3. General Cognitive Decline (Normal Aging)

Normal aging, by contrast, involves mild and infrequent changes. These changes—such as occasionally forgetting a word or misplacing keys—are not severe enough to affect a person's ability to live independently, which distinguishes them from dementia. The process of normal aging tends to be very gradual.

4. Mild Cognitive Impairment

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is an intermediate stage between normal ageing and dementia. In MCI, cognitive changes are noticeable but not yet severe enough to cause disability or interfere with daily activities. People with MCI may or may not eventually develop dementia.

The Core Biology of Alzheimer’s Progression

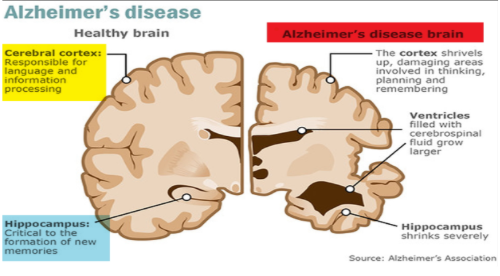

The progression of Alzheimer's disease is caused by specific biological processes that start many years before clinical symptoms appear. The main pathology involves the abnormal build-up and toxicity of two key proteins, leading to neuron dysfunction and death.

The Primary Biological Drivers

1. Amyloid Plaques (Beta-Amyloid) - These structures are clusters formed by a protein fragment called beta-amyloid. They specifically accumulate in the gaps between nerve cells (neurons). The presence of these plaques hampers essential cellular functions and communication between neurons in the brain.

2. Neurofibrillary Tangles (Tau) - These tangles are abnormal accumulations of the protein called tau. Unlike plaques, tangles develop inside the neurons. Their damage process involves disrupting the neuron's internal transport system, a vital structure that moves nutrients throughout the cell, ultimately leading to the cell's malfunction and death.

2. Neurofibrillary Tangles (Tau) - These tangles are abnormal accumulations of the protein called tau. Unlike plaques, tangles develop inside the neurons. Their damage process involves disrupting the neuron's internal transport system, a vital structure that moves nutrients throughout the cell, ultimately leading to the cell's malfunction and death.

Resulting Brain Damage

The combined protein pathologies lead to the loss of neuronal connections. Over time, this cell death results in visible brain shrinkage, known as brain atrophy. The parts of the brain typically affected first are those responsible for memory, including the hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex.

Pharmacological Interventions and Cutting-Edge Research

Although there is currently no cure for Alzheimer's disease, treatments and support focus on managing symptoms and, increasingly, addressing the underlying pathology.

Established Symptomatic Treatments

Standard pharmacological treatment includes medications that aim to temporarily alleviate symptoms by enhancing neurotransmitter activity.

1. Cholinesterase Inhibitors (e.g., donepezil, rivastigmine) assist in increasing chemical messengers in the brain that are involved in memory and judgment.

2. Memantine operates via a different mechanism and is usually prescribed in moderate to severe stages of the disease.

1. Cholinesterase Inhibitors (e.g., donepezil, rivastigmine) assist in increasing chemical messengers in the brain that are involved in memory and judgment.

2. Memantine operates via a different mechanism and is usually prescribed in moderate to severe stages of the disease.

Disease-Modifying Therapies (DMTs)

Current research and newly approved treatments confirm that slowing disease progression requires targeting the protein accumulations (amyloid and tau). The most significant breakthroughs involve monoclonal antibodies that target these proteins.

1. Targeting Amyloid: Therapies such as monoclonal antibodies (lecanemab and donanemab) are intended to harness the body's immune system to eliminate the toxic beta-amyloid protein deposits. Clinical trials have shown that these newer anti-amyloid drugs can slightly slow the progression of cognitive decline in people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease. They mark a significant step forward because they address the fundamental biology of the disease.

1. Targeting Amyloid: Therapies such as monoclonal antibodies (lecanemab and donanemab) are intended to harness the body's immune system to eliminate the toxic beta-amyloid protein deposits. Clinical trials have shown that these newer anti-amyloid drugs can slightly slow the progression of cognitive decline in people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease. They mark a significant step forward because they address the fundamental biology of the disease.

- Challenges: These treatments are administered via infusion and present specific risks, most notably Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA), which can include small bleeds or swelling in the brain. They are mainly recommended for people in the very early stages of the disease who have confirmed amyloid.

2. Targeting Tau: Other emerging therapies, including some in clinical trials (e.g., hydro methylthionine mesylate, or HMTM), aim to prevent the formation and spread of tau tangles.

Emerging Biological Avenues

Scientists are investigating mechanisms beyond plaques and tangles, opening up entirely new avenues for diagnosis and treatment.

1. Metabolism and Inflammation Focus: Researchers identify a link between insulin resistance and brain health, resulting in Alzheimer's being called "Type 3 Diabetes." Investigators are examining medications that enhance insulin sensitivity (such as existing diabetes and weight-loss drugs like Semaglutide) to determine if they can protect brain cells and slow Alzheimer's progression.

2. Waste clearance: Research focuses on enhancing the brain's innate ability to eliminate waste. This involves activating the function of immune cells called microglia, which serve as the brain's "cleanup crew" to remove plaques and debris.

3. The Lithium Link: New research indicates that lithium, a naturally occurring element, is depleted in the brain because it binds to toxic amyloid plaques. This depletion could accelerate the development of AD in mouse models. Ongoing testing with new lithium compounds aims to bypass the plaques, successfully reversing damage and restoring memory in mice, thus offering a potentially new approach for diagnosis and treatment.

1. Metabolism and Inflammation Focus: Researchers identify a link between insulin resistance and brain health, resulting in Alzheimer's being called "Type 3 Diabetes." Investigators are examining medications that enhance insulin sensitivity (such as existing diabetes and weight-loss drugs like Semaglutide) to determine if they can protect brain cells and slow Alzheimer's progression.

2. Waste clearance: Research focuses on enhancing the brain's innate ability to eliminate waste. This involves activating the function of immune cells called microglia, which serve as the brain's "cleanup crew" to remove plaques and debris.

3. The Lithium Link: New research indicates that lithium, a naturally occurring element, is depleted in the brain because it binds to toxic amyloid plaques. This depletion could accelerate the development of AD in mouse models. Ongoing testing with new lithium compounds aims to bypass the plaques, successfully reversing damage and restoring memory in mice, thus offering a potentially new approach for diagnosis and treatment.

Comprehensive Care and Rehabilitation

With no definitive cure for dementia currently available, rehabilitation and high-quality post-diagnostic support are considered essential parts of care, providing individuals with the best chance to live well and stay connected with their community for longer.

Rehabilitation and Reablement

Rehabilitation, often called reablement, concentrates on what a person can still do. This proactive approach aims to help people with dementia maintain their independence, cut down hospital visits, and delay the need for residential aged care.

1. Reablement Activities: These might include exercises to maintain strength and balance, occupational therapy to assist with daily tasks, memory strategies to support independence, or activities that encourage social connection.

2. Support Pathways (Australia): Services are accessible via aged care and health programs. These include:

1. Reablement Activities: These might include exercises to maintain strength and balance, occupational therapy to assist with daily tasks, memory strategies to support independence, or activities that encourage social connection.

2. Support Pathways (Australia): Services are accessible via aged care and health programs. These include:

- Commonwealth Home Support Programme (CHSP): Provides entry-level supports with a focus on wellness, such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or group exercise classes.

- Home Care Packages: Funds can be used for allied health services, as well as home modifications or equipment that support independence.

- Short-Term Restorative Care Program: Offers up to 8 weeks of intensive, goal-based therapy, either at home or in a short residential stay, designed to slow or reverse functional decline.

Specialised Residential Care Models

When a person’s needs exceed safe home management, modern, high-quality residential care often involves specific, evidence-based practices within Specialist Dementia Care Units (SDCUs) or Memory Care Units.

1. Person-Centred Care (PCC) PCC is considered the gold standard, shifting the focus from the disease to the individual.

- Individualised Plans: Care staff learns each resident’s life history, cultural background, hobbies, routines, and preferences, and tailors the care plan based on this knowledge.

- Dignity and Respect: The fundamental idea is acknowledging that the person's individual personality stays intact even as their cognitive abilities fade.

2. The therapeutic environment: the physical layout of the care facility is used as a treatment tool.

- Wayfinding: Units are designed to be intuitive, with secure, circular walking paths, clear signage using pictures and simple text, and recognisable landmarks to reduce anxiety and confusion.

- Sensory Design: The environment uses calming colours and quality, non-glare lighting to reduce "shadowing" confusion.

- Secure Outdoor Spaces: Access to tranquil gardens or courtyards is essential, as these spaces help regulate sleep cycles through vital sunlight exposure, reduce agitation, and allow for freedom of movement.

3. Non-Pharmacological Interventions (NPIs)

High-quality care depends greatly on NPIs to address the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD)—such as agitation, aggression, or anxiety—rather than relying solely on sedative medications.

1. Music Therapy - Using familiar music, singing, or playing instruments. It has the strongest evidence among sensory interventions for reducing anxiety and depression and increasing engagement, especially for people with moderate dementia.

2. Validation Therapy involves the caregiver validating the emotions behind a person’s distorted reality (e.g., "You must miss your mother very much"), rather than correcting them logically. It is used to reduce distress and agitation by connecting with the person's emotional experience.

3. Reminiscence Therapy involves discussing past events, people, and places using tangible aids such as photos or favourite objects. It helps validate the person's life story, boosts self-esteem, and can enhance communication and mood.

4. Sensory Interventions - Techniques like aromatherapy (e.g., lavender), hand massages, or multi-sensory rooms (Snoezelen). They can offer short-term calming and help reduce distress, especially in advanced dementia, where other communication methods are challenging.

1. Music Therapy - Using familiar music, singing, or playing instruments. It has the strongest evidence among sensory interventions for reducing anxiety and depression and increasing engagement, especially for people with moderate dementia.

2. Validation Therapy involves the caregiver validating the emotions behind a person’s distorted reality (e.g., "You must miss your mother very much"), rather than correcting them logically. It is used to reduce distress and agitation by connecting with the person's emotional experience.

3. Reminiscence Therapy involves discussing past events, people, and places using tangible aids such as photos or favourite objects. It helps validate the person's life story, boosts self-esteem, and can enhance communication and mood.

4. Sensory Interventions - Techniques like aromatherapy (e.g., lavender), hand massages, or multi-sensory rooms (Snoezelen). They can offer short-term calming and help reduce distress, especially in advanced dementia, where other communication methods are challenging.

4. Clinical Communication and Staff Training

Effective support requires specialised communication and trained staff. Staff in dementia-specific units are trained to understand behaviour as communication, looking for the "unmet need" behind actions (e.g., wandering might be an attempt to fulfil a past routine, such as "going home from work").

Key communication strategies include speaking slowly and clearly, using simple sentences, and validating the patient's feelings instead of arguing or forcing "reality orientation". Maintaining a consistent daily routine and using simple visual cues (like labelled drawers) can reduce confusion and agitation. Furthermore, high-quality units aim to minimise restraints—physical or chemical—by relying on environmental modifications and behavioural strategies.

Effective support requires specialised communication and trained staff. Staff in dementia-specific units are trained to understand behaviour as communication, looking for the "unmet need" behind actions (e.g., wandering might be an attempt to fulfil a past routine, such as "going home from work").

Key communication strategies include speaking slowly and clearly, using simple sentences, and validating the patient's feelings instead of arguing or forcing "reality orientation". Maintaining a consistent daily routine and using simple visual cues (like labelled drawers) can reduce confusion and agitation. Furthermore, high-quality units aim to minimise restraints—physical or chemical—by relying on environmental modifications and behavioural strategies.

Conclusion

The distinction between dementia (the disabling syndrome) and Alzheimer’s disease (the specific progressive neuropathology driven by amyloid and tau) is crucial for precision medicine. While groundbreaking pharmacological treatments now offer the ability to modestly slow cognitive decline by targeting underlying amyloid pathology, the long-term management of AD and other dementias remains fundamentally reliant on integrated, patient-centred support. The commitment to reablement, environmental modification, and the use of non-pharmacological interventions provides the essential framework for optimising dignity, independence, and quality of life for individuals navigating this neurodegenerative frontier.

Interested in reading more blogs? Visit the HUB, IPS’s website

Contact us at support@infectionprevention.care

We are on Facebook and LinkedIn – like, share and follow

For a quick answer to a short question, talk to EVE, our multilingual “bot”.

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

We are on Facebook and LinkedIn – like, share and follow

For a quick answer to a short question, talk to EVE, our multilingual “bot”.

Take advantage of our expertise in IPC. See the HUB for policies, resources and courses relating to this very important subject. Ask EVE for a quick answer to your question.

Lyndon Forrest

Managing Director | CEO

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

I am a passionate and visionary leader who has been working in the field of infection prevention and control in aged care for almost 30 years. I am one of the co-founders and the current Managing Director and CEO of Bug Control New Zealand and Australia, the premium provider of infection prevention and control services in aged care. I lead a team that is driven by a common purpose: to help aged care leaders and staff protect their residents from infections and create a healthier future for them.

I am building a business that focuses on our clients and solving their problems. We are focused on building a world-class service in aged care. We focus on being better, not bigger, which means anything we do is for our clients.

Erica Callaghan

Marketing Manager

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Erica Callaghan is a dedicated professional with a rich background in agriculture and nutrient management. Growing up on her family's farm in Mid Canterbury, she developed a deep passion for farming. She currently resides on her partner's arable property in South Canterbury.

In 2017, Erica joined the Farm Sustainability team, focusing on nutrient management and environmental stewardship. In February 2024, she became the Manager of Marketing and Sales at Bug Control New Zealand - Infection Prevention Services, where her passion now includes improving infection prevention outcomes.

Outside of work, Erica loves cooking and traveling, often combining her culinary interests with her explorations in Italy and Vietnam. She enjoys entertaining family and friends and remains actively involved in farm activities, especially during harvest season.

Toni Sherriff

Clinical Nurse Specialist

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Toni is a Registered Nurse with extensive experience in Infection Prevention and Control. Her career began as a kitchen hand and caregiver in Aged Care facilities, followed by earning a Bachelor of Nursing.

Toni has significant experience, having worked in Brisbane’s Infectious Diseases ward before returning home to New Zealand, where she continued her career as a Clinical Nurse Specialist in Infection Prevention and Control within Te Whatu Ora (Health NZ).

Toni brings her expertise and dedication to our team, which is instrumental in providing top-tier infection prevention solutions to our clients.

Julie Hadfield

Accounts & Payroll

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Julie is experienced in Accounts & Payroll Administration & after a long career in both the Financial & Local Government Sectors, is now working with our team. Julie brings her strong time management & organisational skills to our team, which is important to keep the company running in the background to enable the rest of our team to provide top notch service to all of our clients.

Andrea Murray

Content Editor

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

I attended Otago University in NZ and graduated as a Dental Surgeon. After 40 years in the profession, I retired in 2022. Infection prevention knowledge was part of everyday practice, dealing with sterilisation, hand hygiene, and cleaning.

Before retiring, I began doing some editing and proofreading for Bug Control as I am interested in the subject and in the English language. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I attended the ACIPC course "Introduction to Infection Prevention and Control", which increased my interest in the subject. I now work part-time as the Content Editor for the company.

Personally, I lived in the UK for 10 years. My two children were born in Scotland, and now both are living in Europe, one in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. I live close to Fairlie on the South Island of NZ, a beautiful part of the country, and I love being out of the city.

Princess

Customer Support

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Princess began her career as a dedicated Customer Service Representative, honing her communication and problem-solving skills. She later transitioned into a Literary Specialist role, where she developed a keen eye for detail. Her journey then led her to a Sales Specialist position, where she excelled in client relations.

Now, as a Customer Support professional in Infection Prevention Services. Princess focuses on ensuring customer satisfaction, building loyalty, and enhancing the overall customer journey.

Dianne Newey

Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

With over 35 years of experience as a Registered Nurse, I'm now applying all my experience and skills as a Senior Infection Prevention and Control Consultant with Bug Control Infection Prevention Advisory Services.

In my role, I promote Infection Prevention and Control, to RACF's and disability support services.

This is through IP&C education, IP&C environmental audits and reports, IP&C policy and procedure review and development and consultancy on infection prevention and control issues. When I’m not working, I spend time with my family and in my garden, where I grow all my own veggies.

Caoimhe (Keva) Stewart

Clinical & Business Operations Manager

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Caoimhe is the Manager of Customer Service at Bug Control | Infection Prevention Services, where she ensures that learners have a seamless and supportive experience. With her previous experience as a Registered Nurse in both the UK and Australia, Caoimhe brings a deep understanding of healthcare to her role. Before joining Bug Control IPS Services, she worked in a variety of nursing settings, including Occupational Health, Palliative Care, and Community Nursing, providing her with the ability to empathise with learners and understand the challenges they face.

Her move from nursing to customer service was driven by her passion for helping others, not just in clinical settings but also in ensuring that people have access to the resources and support they need. Now, Caoimhe applies her problem-solving skills, attention to detail, and communication expertise to her role, helping to create a positive and effective learning environment for all students.

Outside of work, Caoimhe enjoys travelling, staying active, and catching up with friends on the weekends. Whether in healthcare or customer service, she’s dedicated to making a meaningful difference and supporting people in their personal and professional growth.

Bridgette Mackie

Clinical Nurse Educator

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.

Bridgette is an experienced New Zealand Registered Nurse, qualified Healthcare Auditor, and Healthcare Educator with a strong background in clinical quality, competency assessment, and infection prevention. She has led large-scale OSCE and CAP training programmes for internationally qualified nurses, developed sector-specific educational resources, and coordinated HealthCERT audit preparation in the surgical sector.

Known for her engaging teaching style and genuine passion for supporting learners, Bridgette excels at making complex topics accessible and relevant. She blends operational leadership with a deep commitment to professional development and safe, effective practice.